exhibitionLarry Achiampong, Patty Chang, Shezad Dawood, Rhea Dillon, DeSe Escobar, Madelynn Green, Nadya Isabella, Athena Papadopoulos, Mohammed Sami and Urara Tsuchiyahomeplace07.05—12.06.202156 Conduit Street

11:00am—6:00pm56 Conduit Street

A home consists of windows and stairways, of rooms and liminal spaces. Alongside these physical components, a home is also comprised of the lives of its inhabitants: their joys, their fears, their desires. The roof and walls of a home offer its dwellers protection from the weather, but also from the perils of an external world shaped by patriarchy and white domination. In the home, out of the reach of these intersecting systems of power, is where all that truly matters in life takes place: the warmth and comfort of shelter, the feeding of bodies, the nurturing of souls.

V.O Curations is pleased to present homeplace, an exhibition of work by ten artists that rereads the concept of private domesticity as both theory and philosophy. Curated by Kate Wong, the show takes its title from a 1996 essay by bell hooks in which the notion of ‘homeplace’ is understood as the making of a physical as well as a psychic community of resistance. If to resist means to oppose being invaded or destroyed by healing oneself, then homeplace is the creation of a restorative space where those who have been dehumanised outside in the public world can regain ontological wholeness. Emerging through the conscious and heroic labour of black women within the colonised world of white supremacy, and no matter how fragile and tenuous it is, homeplace is vital to liberation struggle. To create and to sustain a place in which black people can affirm themselves despite oppressive socio-political conditions is not only an act of care, but a radically subversive political gesture.

Employing the concept of homeplace as a framework through which to consider the disruptive potentials of domesticity, this exhibition untethers the lexicon of the home from its traditionally passive and feminised position. Tenderness and vulnerability become a form of resistance and instances of slowness and softness become a mode of refusal. In addition to the works by black women and women of colour in the exhibition, homeplace seeks to reveal the often hidden registers of private domestic life across a multiplicity of experiences. Where they overlap, these narratives form the basis for a shared political and cultural imaginary.

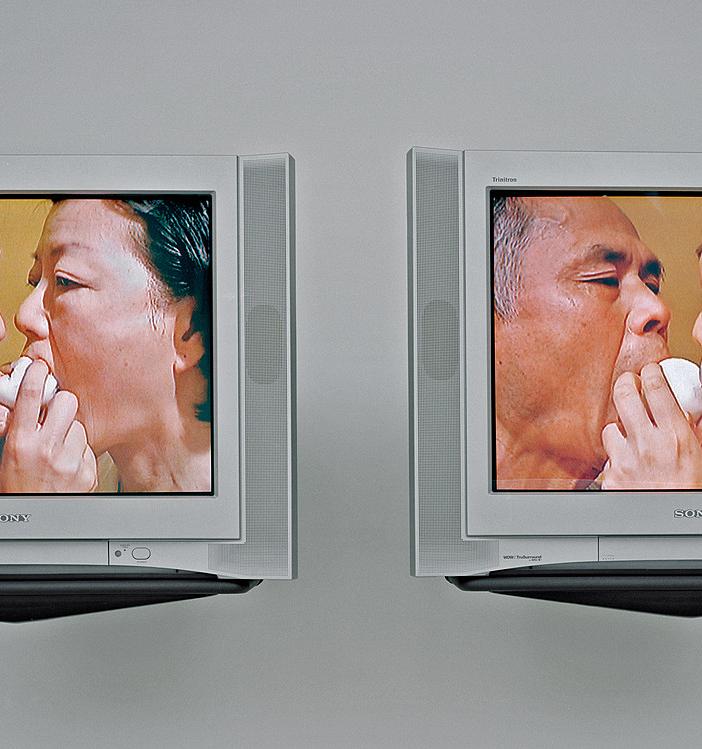

Installed in the main gallery, Korean-American artist Patty Chang’s two-channel film In Love (2001) shows Chang and each of her parents eating an onion. The films run backward so that on each screen the artist appears to be crying while passionately kissing both her mother and father. This disturbing embrace is only revealed to be false when the evidence of an onion appears between them. In Love pairs feelings of longing and desire with conflicting trajectories of pain and loss. The work hints at the unspoken and often bitter feelings that can exist between a parent and child,

while simultaneously alluding to the unconditional nature of familial bonds. In her 2018 painting, The Kitchen, American artist Madelynn Green hazily depicts her two siblings situated around a kitchen countertop laden with quotidian objects. The scene offers a visual muteness that points toward the subtler and more quiet modes of refusal most often ignored by mainstream political thought. Within an installation of four of her works, Japanese artist Urara Tsuchiya’s playful and slightly perverse ceramic sculpture, max mon amour (2020), tells a story of an inter-species relationship between human and chimpanzee, utilising her trademark playfulness as a way to disrupt traditional understandings of intimacy.

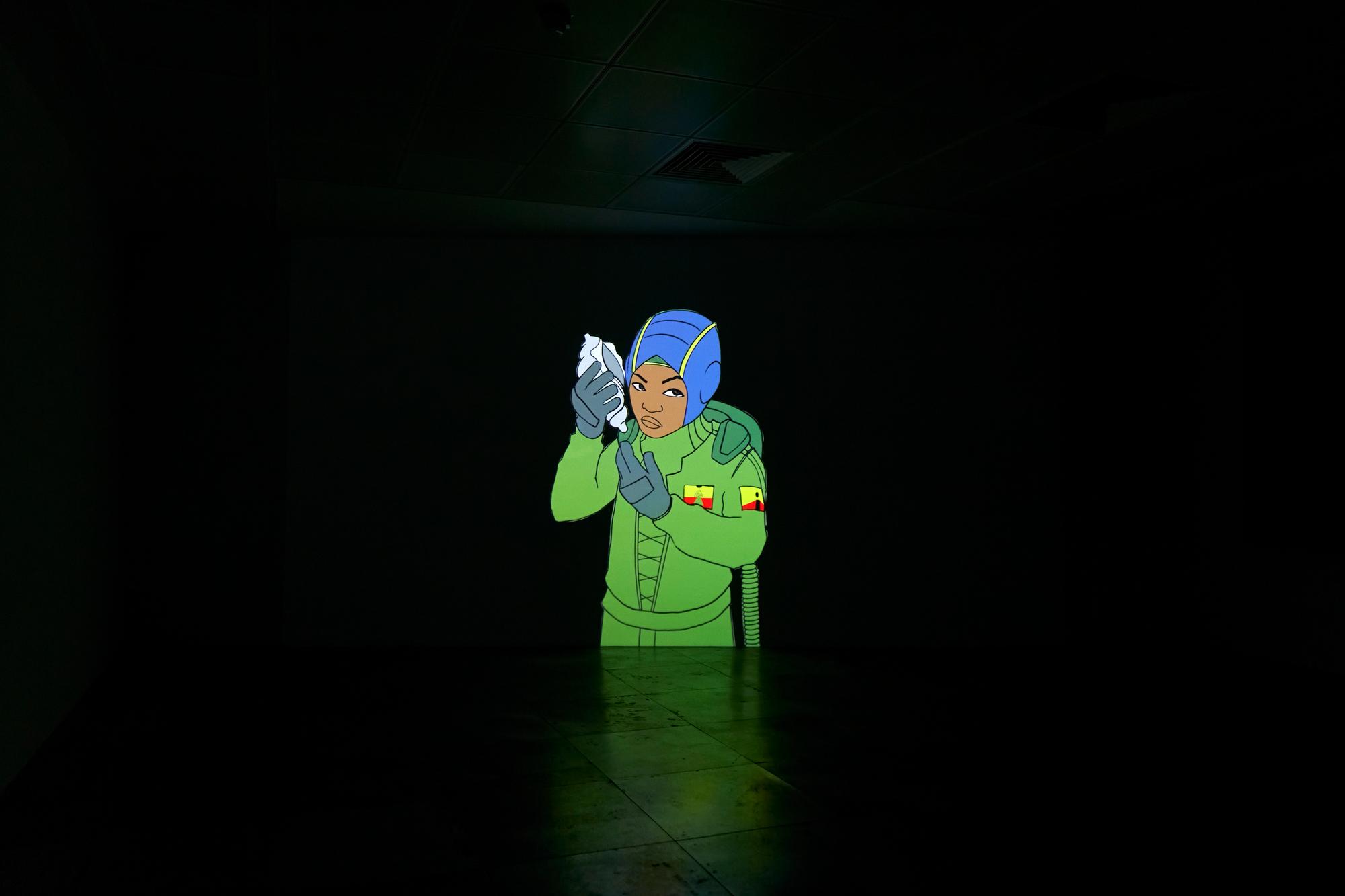

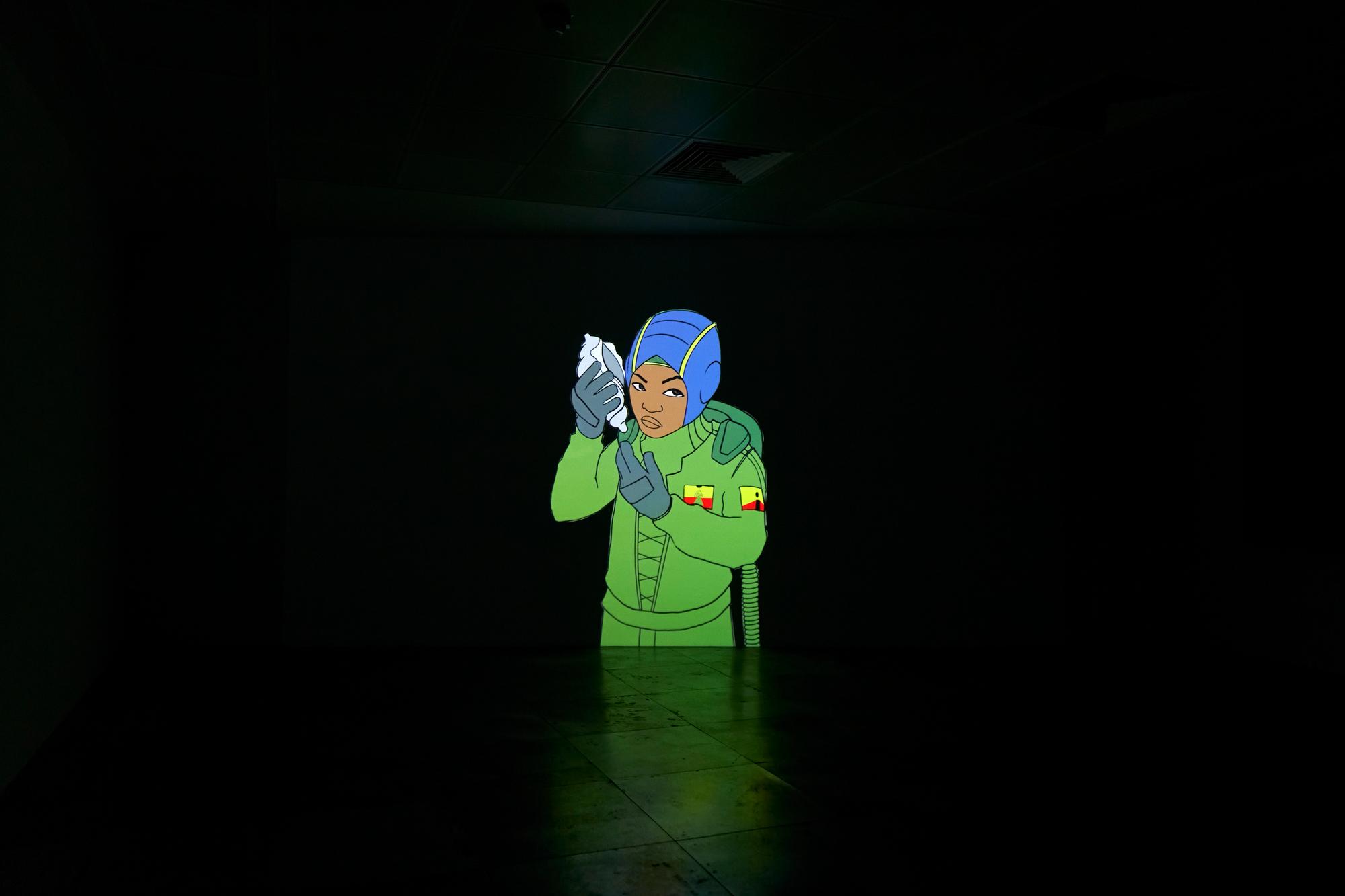

In the second floor project space, Larry Achiampong’s 2020 film Reliquary 2 is a meditation on a period of separation between the artist and his two children during the COVID-19 lockdown. Formed from animated sequences and drone footage that are overlaid with an original score and narration by the artist, the film speaks to the fragility of life, and especially of black life within the context of the pandemic. Achiampong’s film propels the concept of homeplace out of the feminine domain, demonstrating the strength and devotion of a father’s love.

Installed in the project space on the fifth floor, Rhea Dillon’s new and never before seen immersive video essay brings together poethic responses by eight of the artist’s friends and collaborators. The work ruminates on the word and colour, brown, asking: What does it mean to be a brown skinned woman? What does it mean that this colour is consecutively voted the world’s least favourite colour? Who is brown and when do they land?

Rather than provide answers, the works in homeplace pose questions rooted within understandings of home and belonging. The diverse experiences of the ten artists in the show demonstrate private domestic life as not only a place of healing but also as the basis for an interdependent form of refusal. The exhibition demonstrates that the home far exceeds its function as a physical dwelling place, and that it serves critically as the foundation upon which to build a community of resistance.

Finally and most importantly, homeplace acknowledges the fact that it is black feminists who have provided us with so much of the language, the lived experience and the politics to fuel the kinds of imaginaries required to fight for the world we actually need.

Related

artistUrara Tsuchiya

artistUrara Tsuchiya artistPatty Chang

artistPatty Chang artistLarry Achiampong

artistLarry Achiampong artistAthena Papadopoulos

artistAthena Papadopoulos artistMohammed Sami

artistMohammed Sami artistRhea Dillon

artistRhea Dillon artistMadelynn Green

artistMadelynn Green newsArtforum: Gilda Williams at London Gallery Weekend, Homeplace13.06.2021

newsArtforum: Gilda Williams at London Gallery Weekend, Homeplace13.06.2021 newsOcula: Shows to See during London Gallery Weekend, Homeplace02.06.2021

newsOcula: Shows to See during London Gallery Weekend, Homeplace02.06.2021 newsThe ARt Newspaper: Three exhibitions to see in London this weekend, Homeplace 228.05.2021

newsThe ARt Newspaper: Three exhibitions to see in London this weekend, Homeplace 228.05.2021 newsContemporary Art Society: Homeplace at V.O Curations28.05.2021

newsContemporary Art Society: Homeplace at V.O Curations28.05.2021 newsThe ARt Newspaper: Three exhibitions to see in London this weekend, Homeplace 228.05.2021

newsThe ARt Newspaper: Three exhibitions to see in London this weekend, Homeplace 228.05.2021