exhibitionNour el SalehWhere the Grass is Synthetic25.03—01.05.202156 Conduit Street

11:00am—6:00pm56 Conduit Street

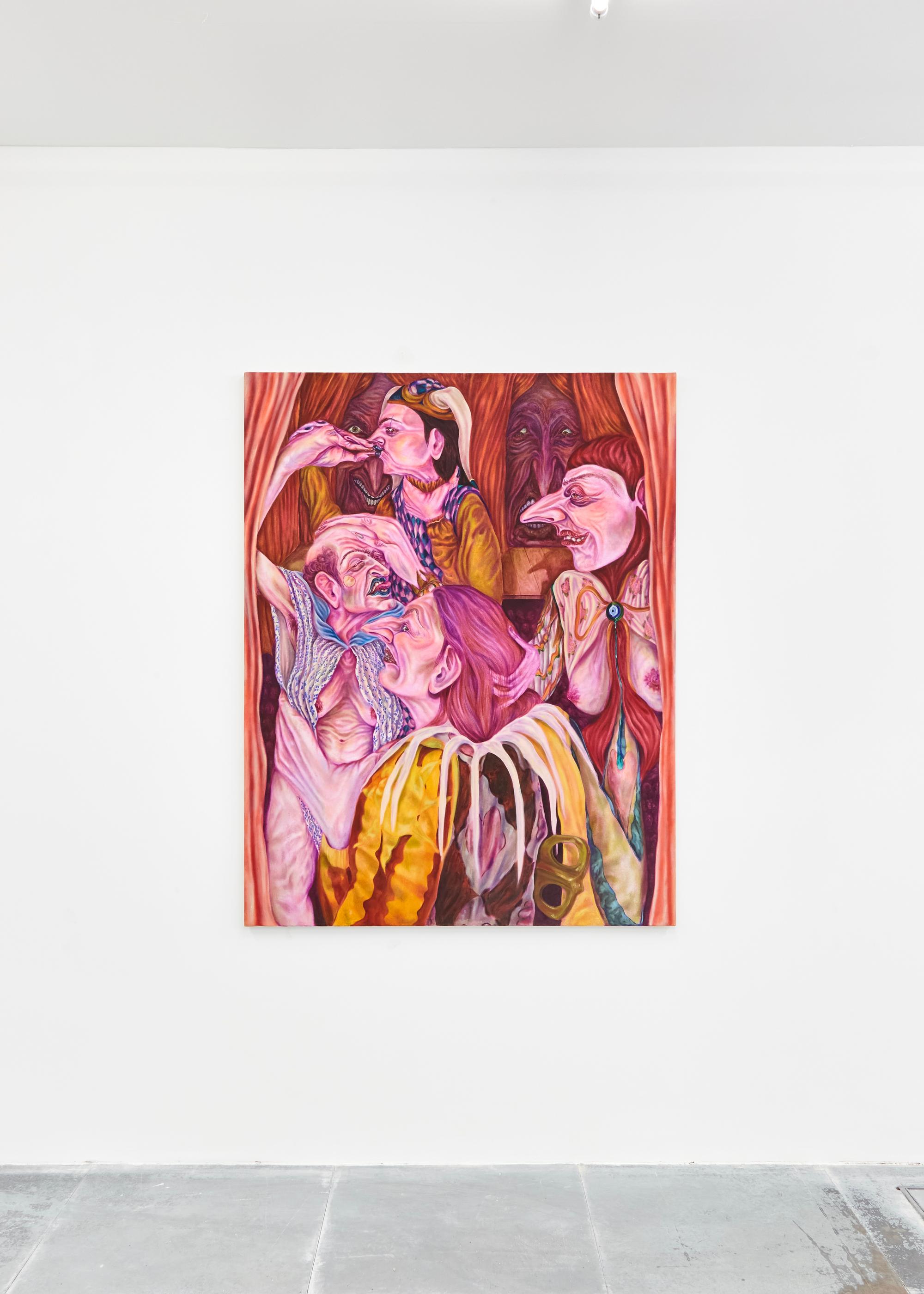

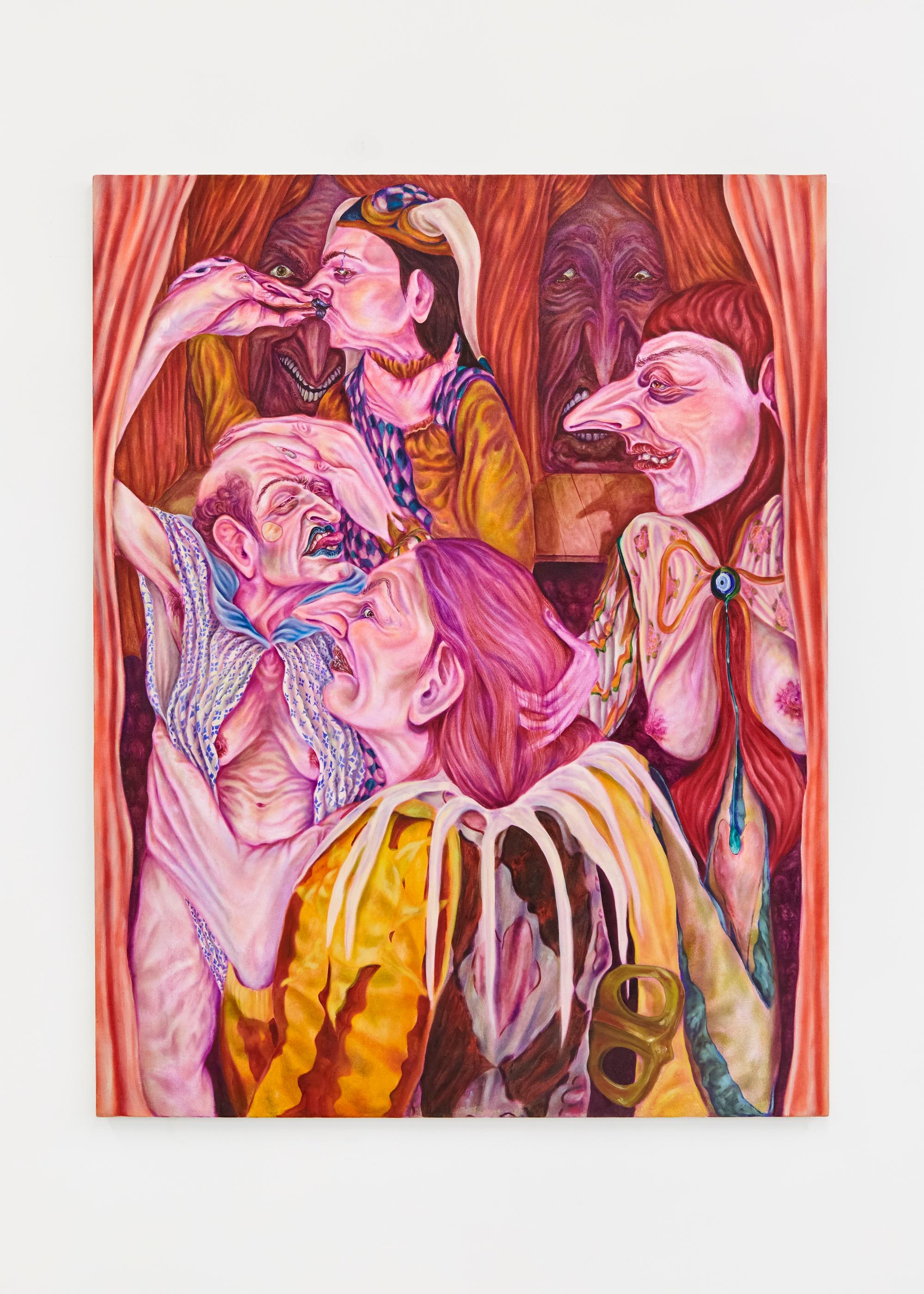

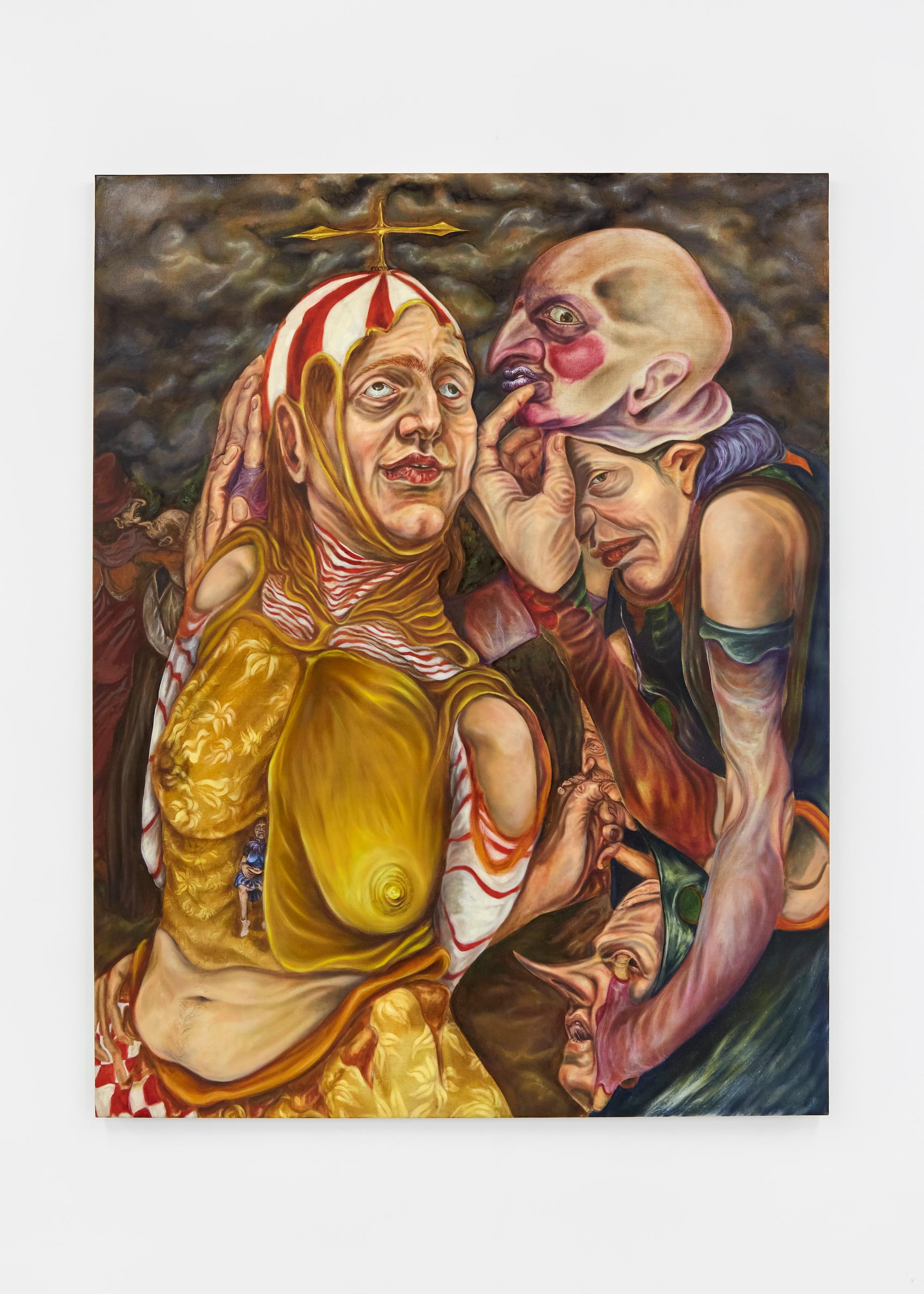

In her second solo exhibition at V.O Curations, London-based Lebanese artist Nour el Saleh presents a group of six new paintings alongside, for the first time, a miniature three-dimensional sculpted painting. Titled Where the Grass is Synthetic, this new body of work sits somewhere between real and dream worlds, employing the theatre as allegory, and as a character in and of herself.

Ugliness is subjective. Like beauty, ugliness is a polysemic concept. Where aesthetic beauty is informed by balance and proportion, by visual harmony, ugliness is informed by imperfection. By chaos.

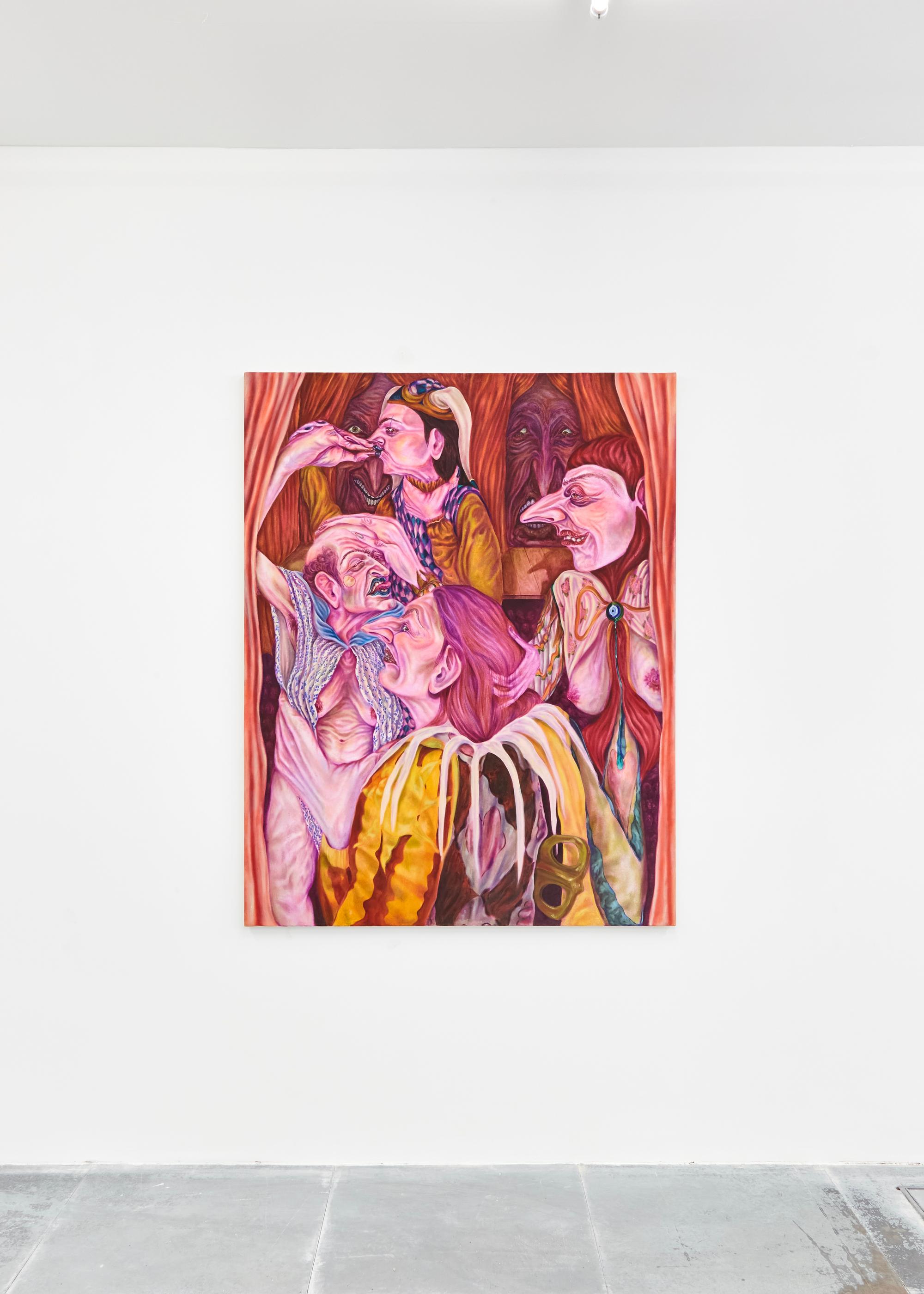

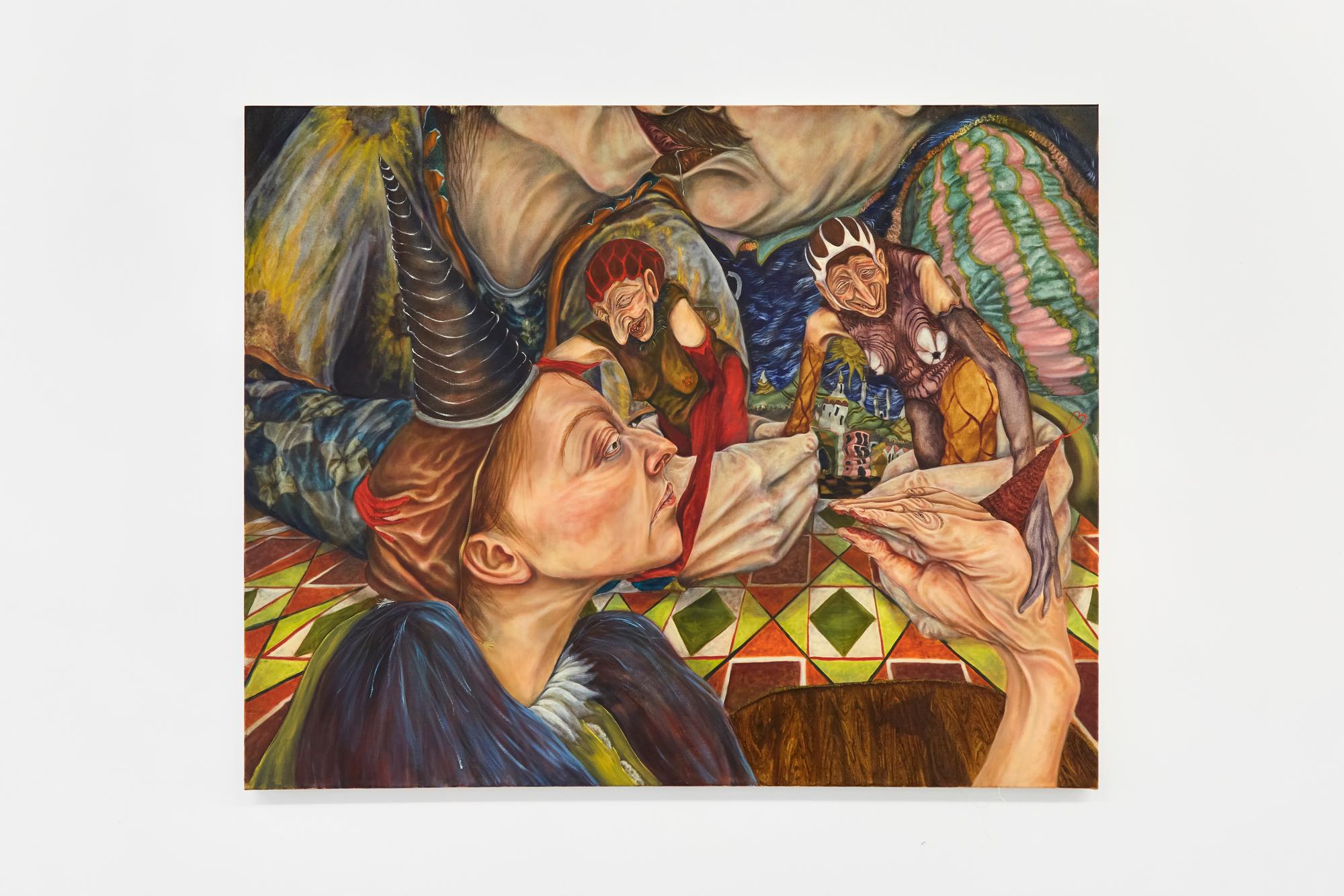

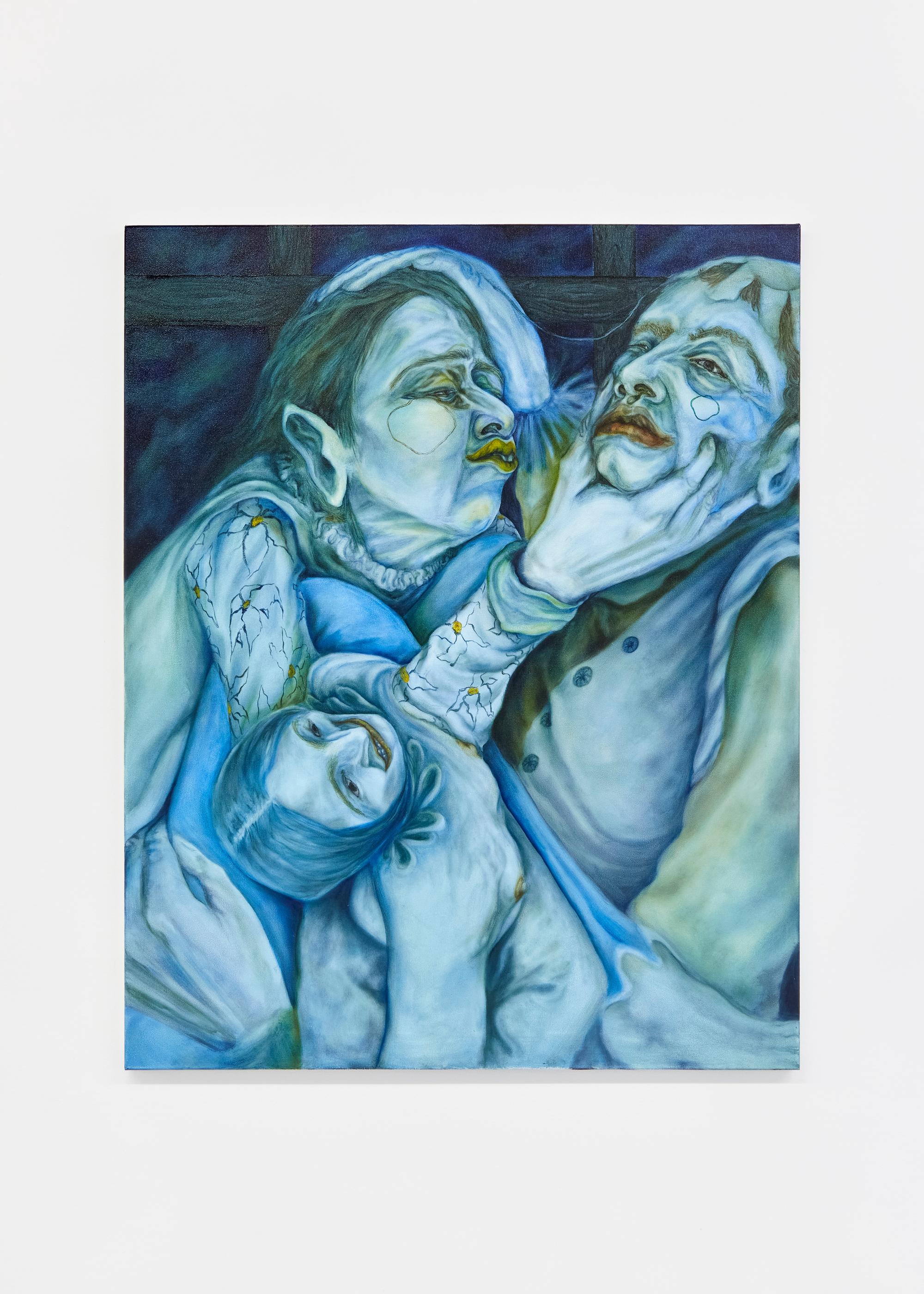

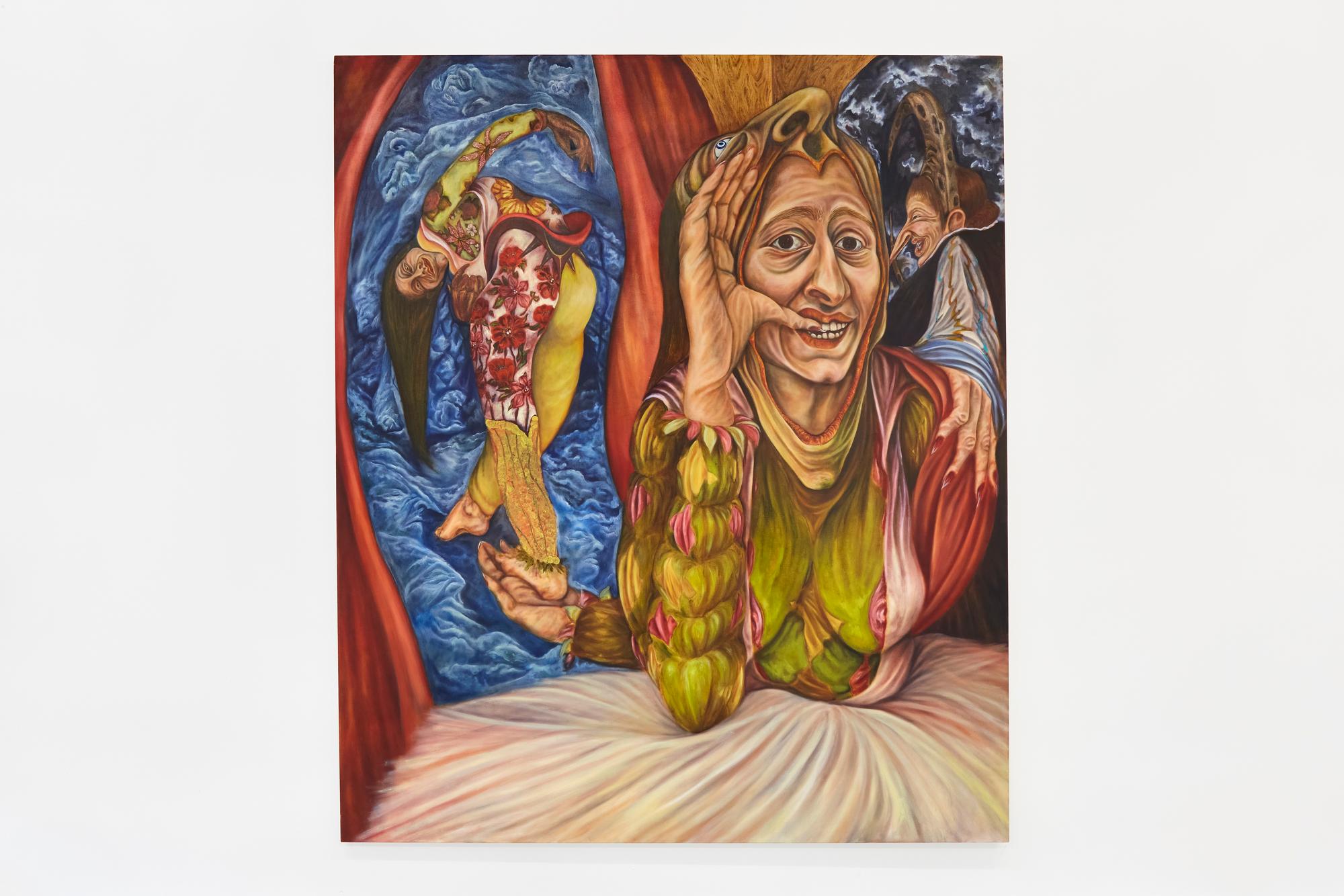

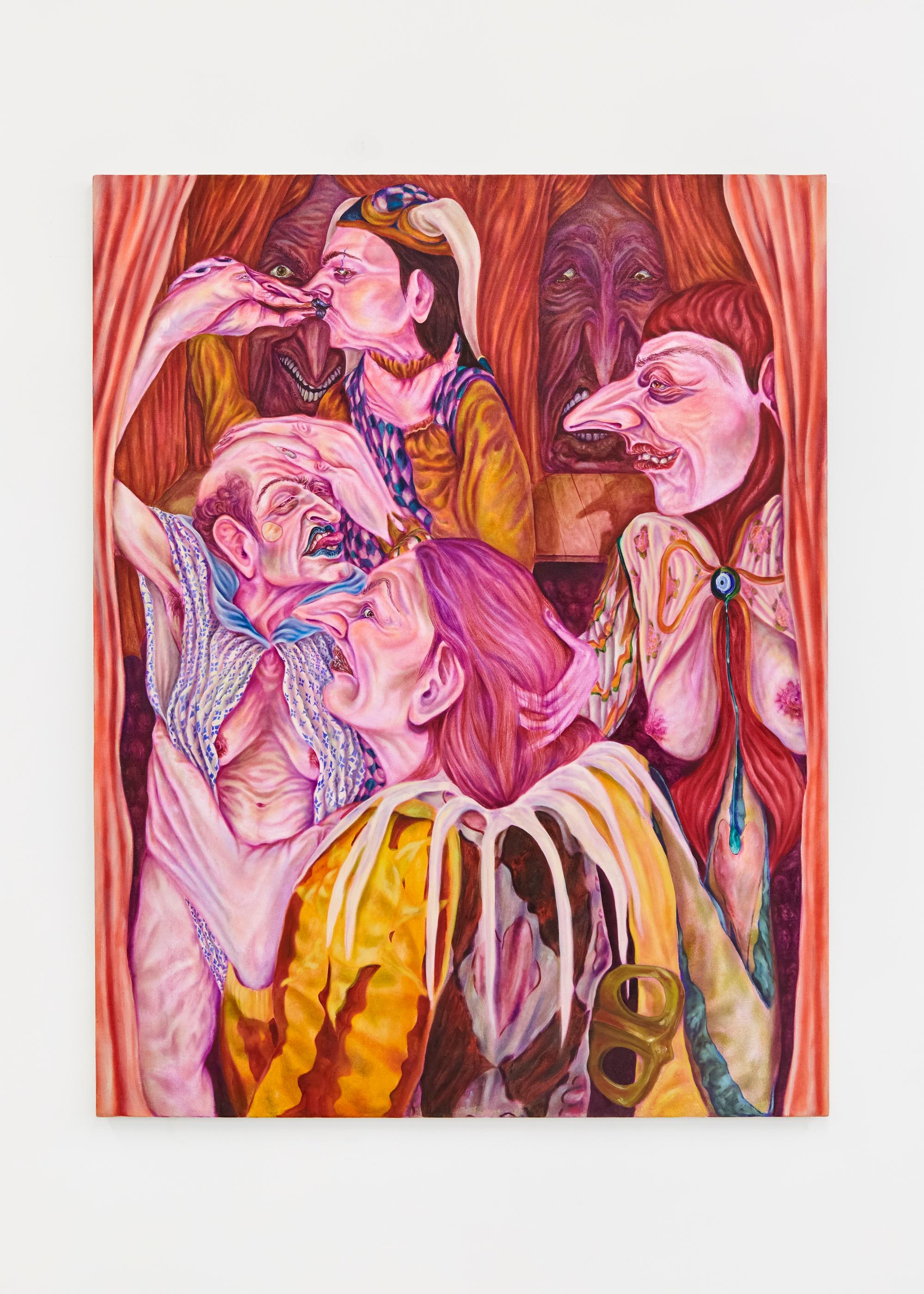

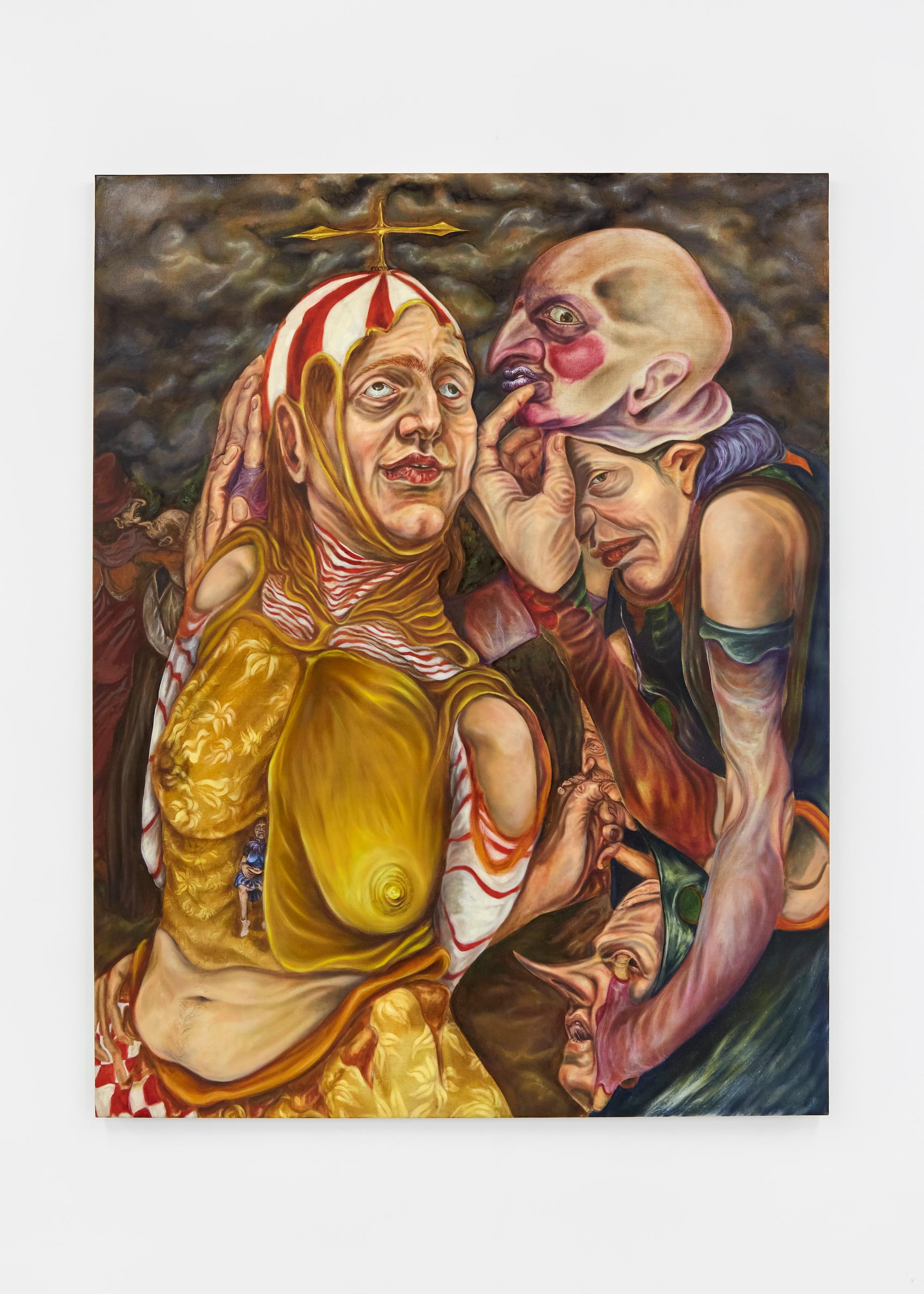

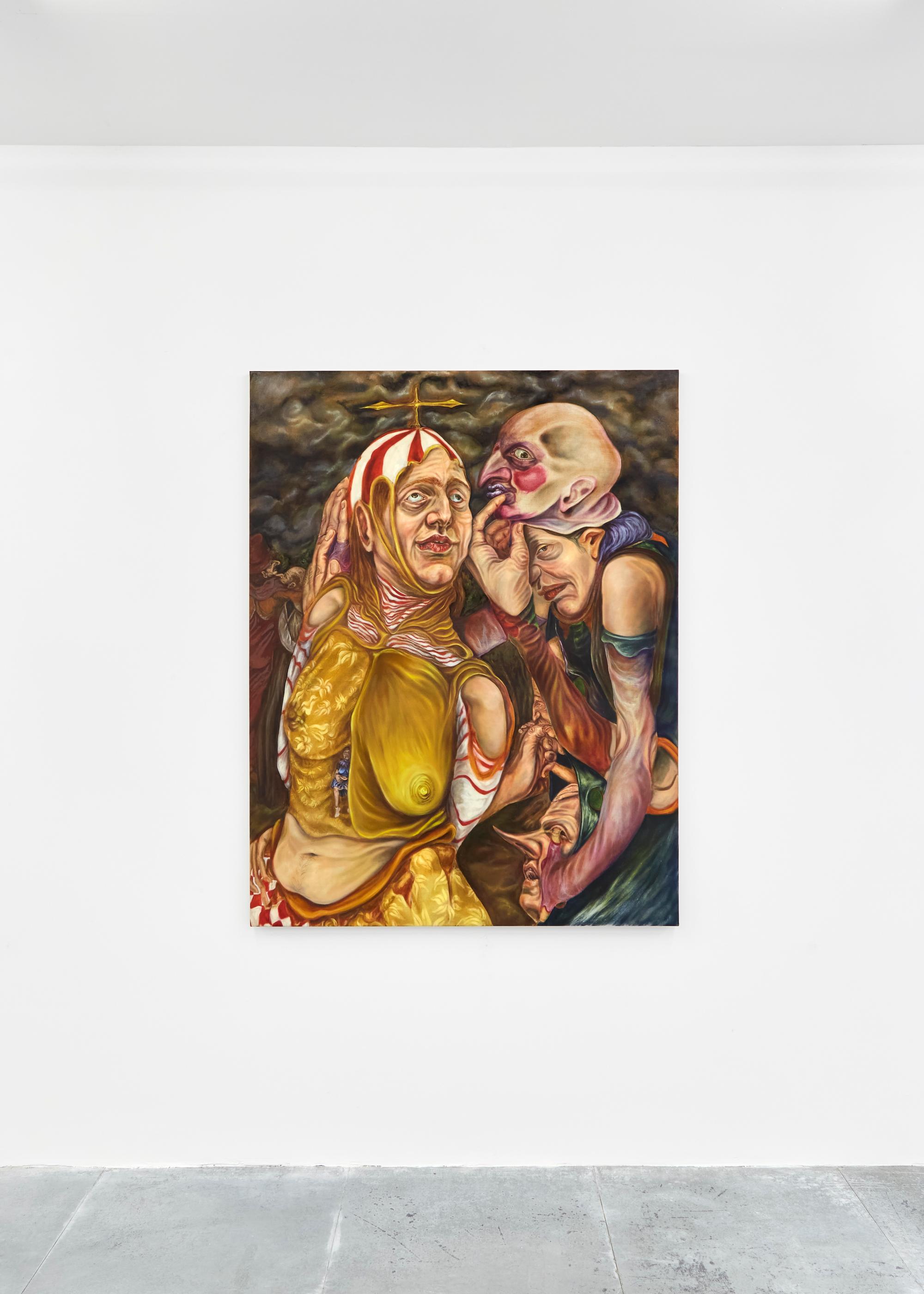

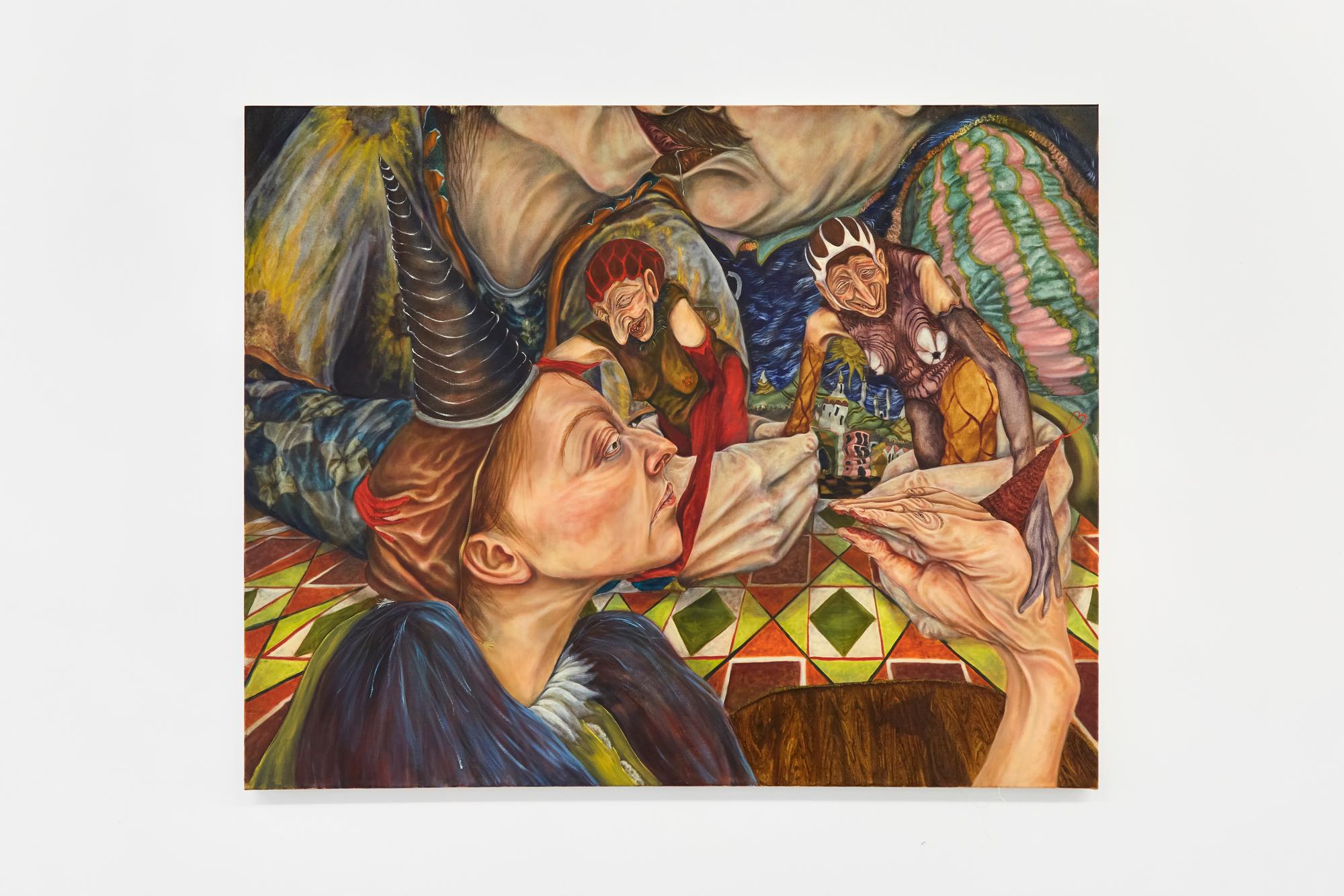

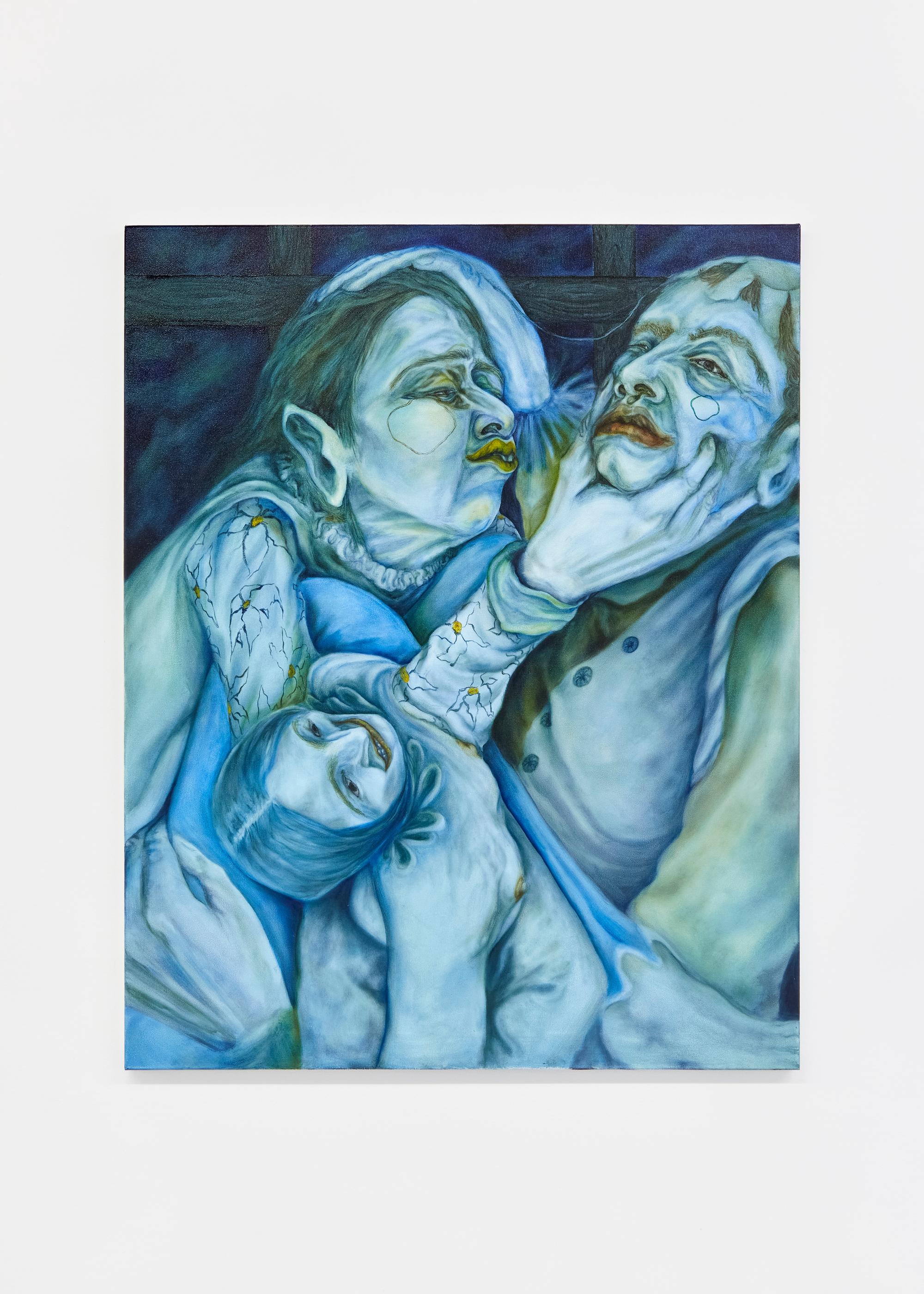

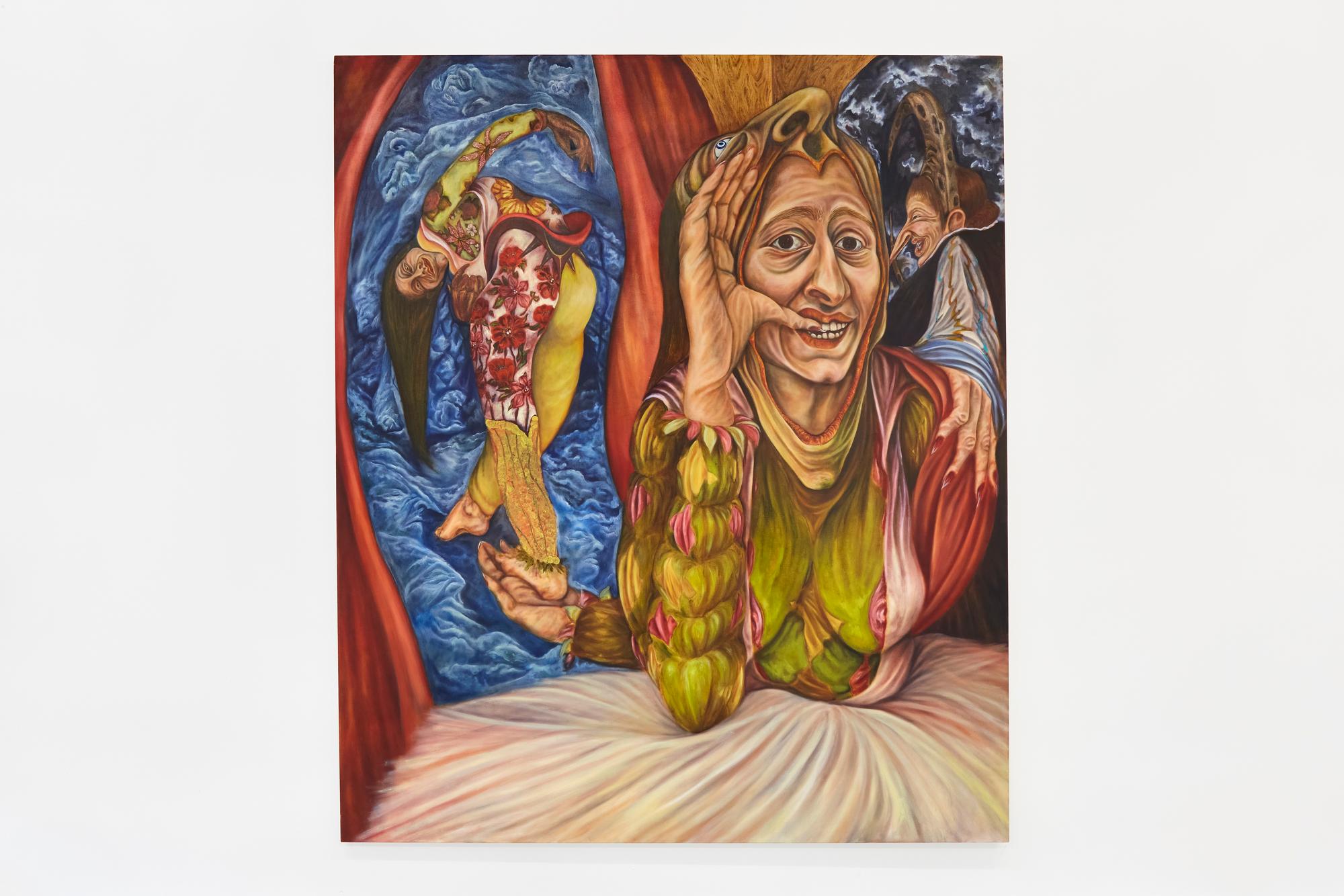

Upon first glance into el Saleh’s incongruous world the viewer is engulfed immediately by her cast of strange and grisly characters. With pallid flesh and gruesome, gaping mouths, the figures are nightmarish. Portrayed with overgrown features and puckers of shrivelled skin, the players in el Saleh’s paintings call to mind Da Vinci’s physiognomical studies of the grotesquely ugly. They are altogether not entirely human. Just as one feels the urge to pull away, however, the viewer is caught off guard by a number of recognisable and even comforting sights: wallpaper depicting fluffy clouds against a blue sky in The Play that Never Was, or a figure’s garments adorned in golden sunflowers in The Actor’s Dollhouse. These tones and textures stand against the macabre, belonging instead to the sacred realm of childhood memory.

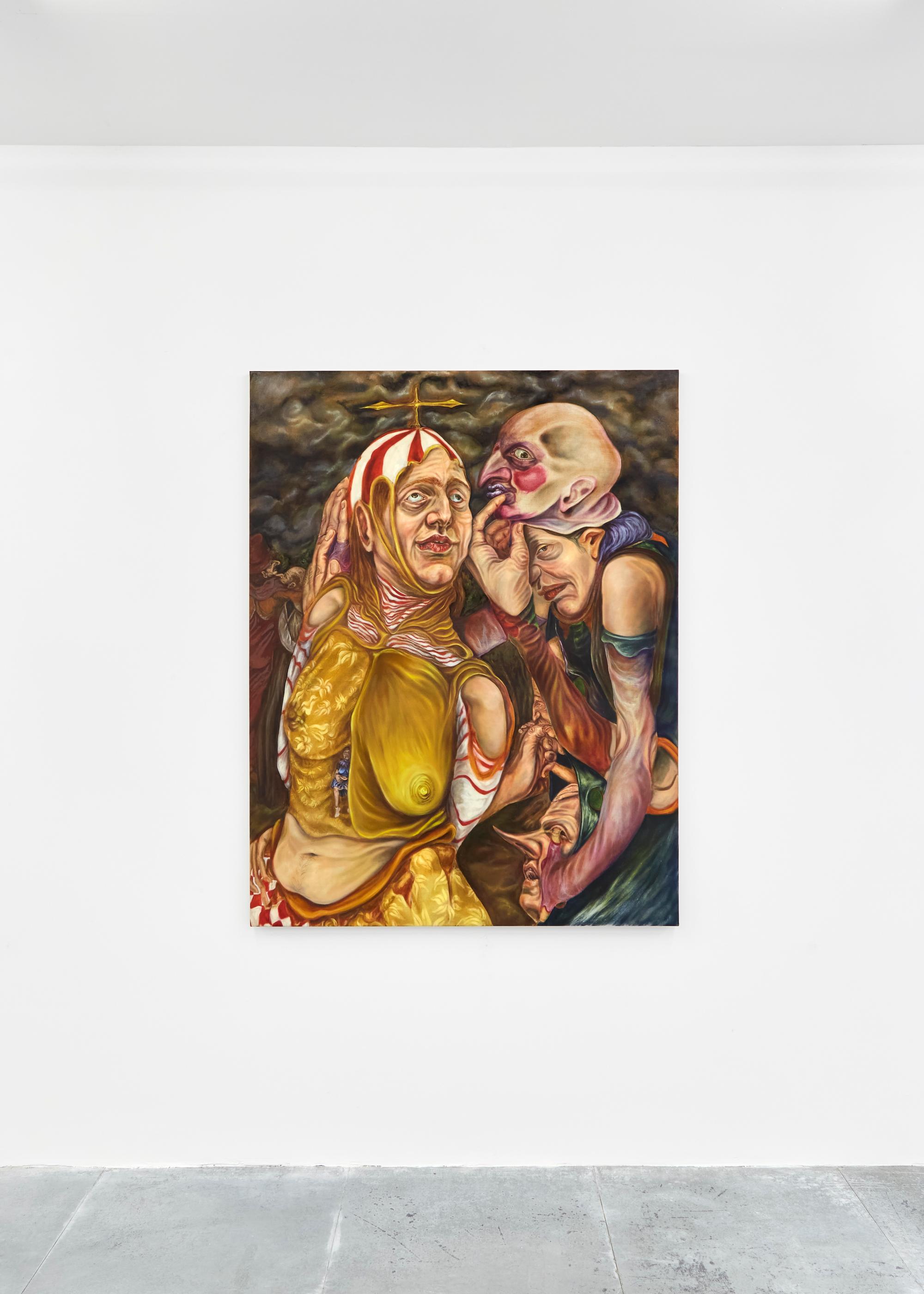

Whether familiar or unfamiliar, el Saleh's canvases are undeniably rich environments. Replete with layered symbolism these are worlds in which traditional commedia dell’arte stock characters have been pulled apart and reassembled as a means of exploring identity and in-betweenness. The figure of the jester or joker appears in different forms across the exhibition both as self-portraiture and as an archetypal figure embodying ugliness as a means to address that which is most despised or feared in society.

El Saleh’s interest in the theatre began early and intensely, and since, has become a conceptual framework and a methodology for the construction of a new visual language.

The focus, instead of being on leading roles, falls on supporting characters. These figures who are traditionally snubbed and confined to the dusty wings of the stage are pushed to the forefront, emerging centre stage under the care of el Saleh’s paintbrush, and rendered in brilliant colour.

Rather than to shy away from storytelling, the artist’s work confronts head on the notion of narrative within contemporary painting. Co-opting the dramatic visual signifiers of Western European religious painting, el Saleh has developed her own visual lexicon with which to articulate that which is culturally Arabic. In Portrait of Pious the central figure gazes upwards with a cross-like object on their head and an expression of otherworldly ecstasy. The tempestuous sky is rendered in deep umber calling to mind Heironomous Bosch’s apocalyptic Dutch Renaissance paintings. In the exhibition’s titular painting two faerie-like figures can be read as Lebanese aunties, at once welcoming - beckoning with their insistent hands - but all the while playing the role of the gossip.

El Saleh’s work is generous. She provides infinite entry points into her chaotic imagined worlds, playing with aesthetic ugliness as a way to confront alterity, and ultimately, change. If ugliness is in the eye of the beholder what can we learn from sitting with the grotesque? And existing outside of the purview of beauty, is this state of irregularity and chaos perhaps the most generative place for us to be?