exhibitionRhea DillonNonbody Nonthing No Thing15.10—11.11.202156 Conduit Street

11:00am—6:00pm56 Conduit Street

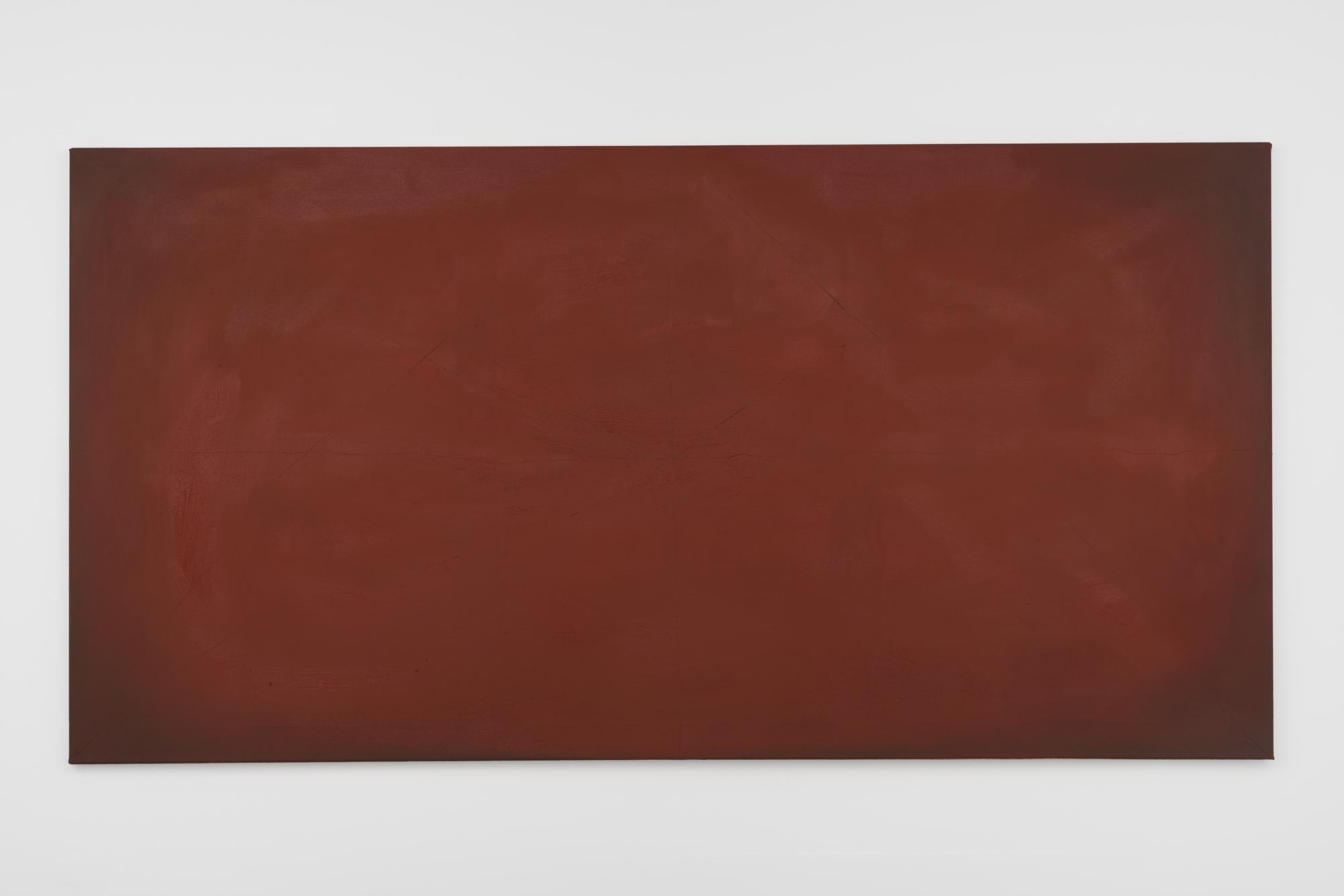

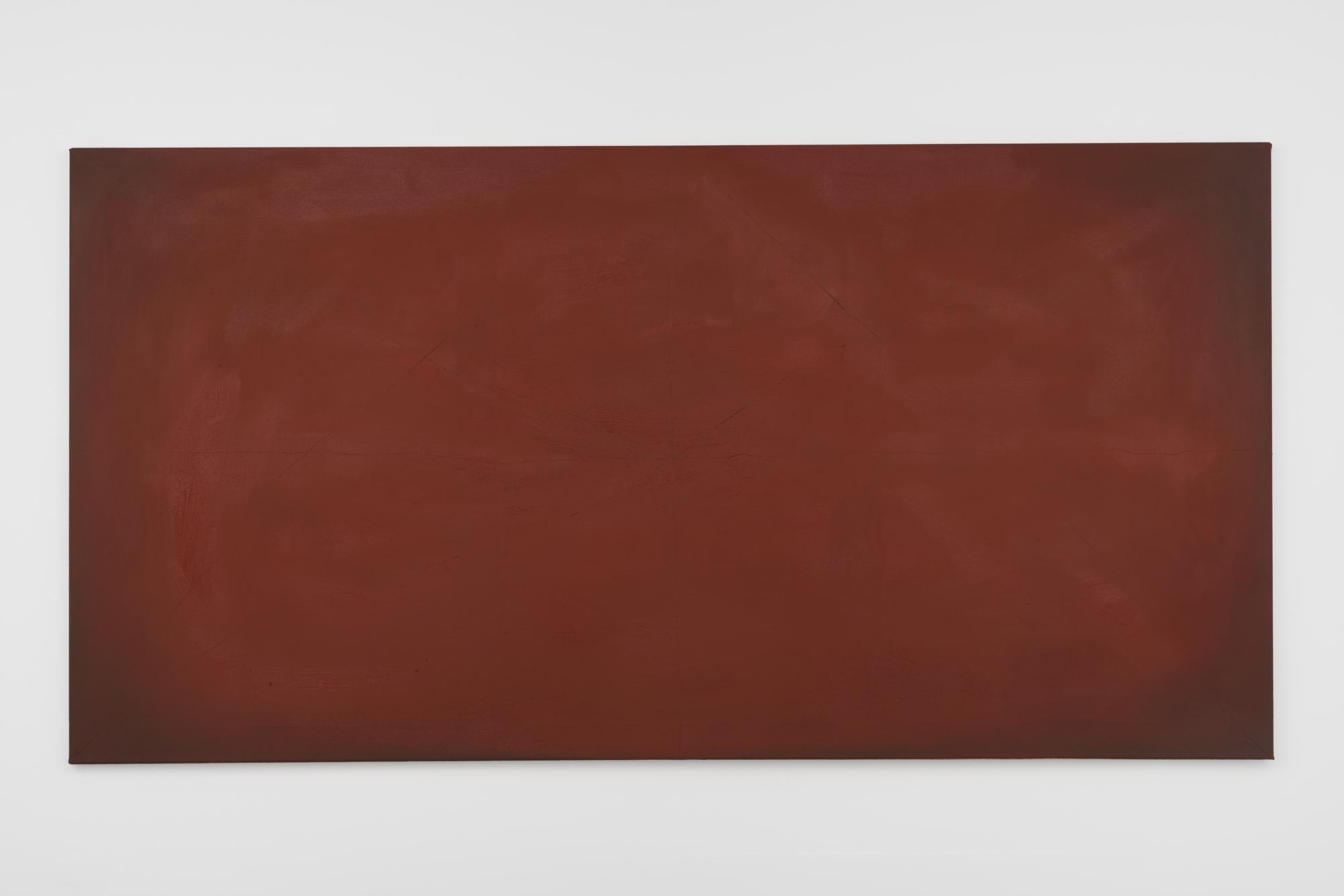

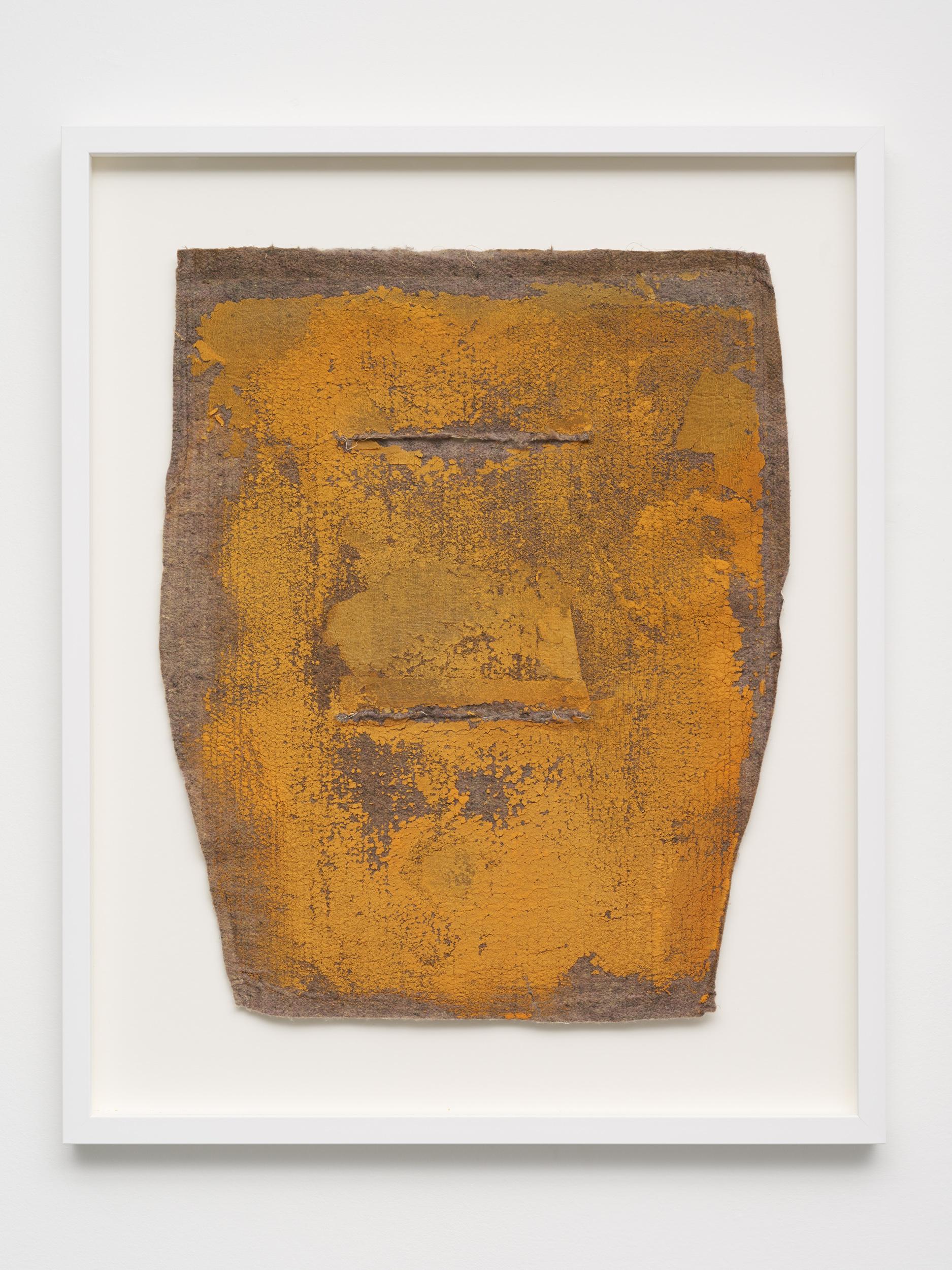

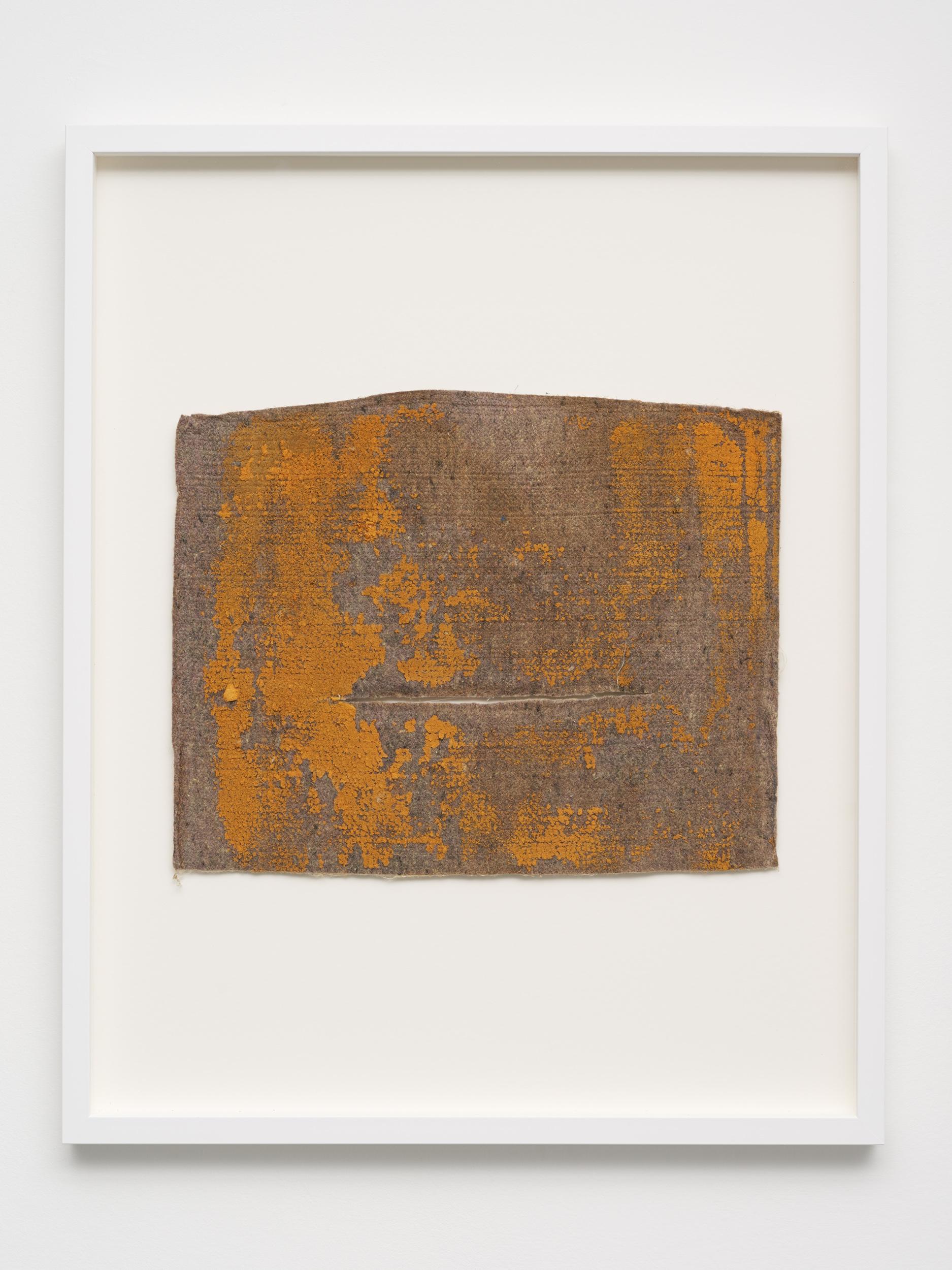

Pitch black anti-climb paint recedes cavernously into orange bus seats that rise like mountains. The same dark nothingness coats the inside of a mirrored dome that forms part of a sculpture suspended by metal chains, halfway between the ceiling and the floor of the gallery. In this second application the black paint sits slicker. Sticky, wet and thick, it transforms the belly of the dome into an oceanic abyss.

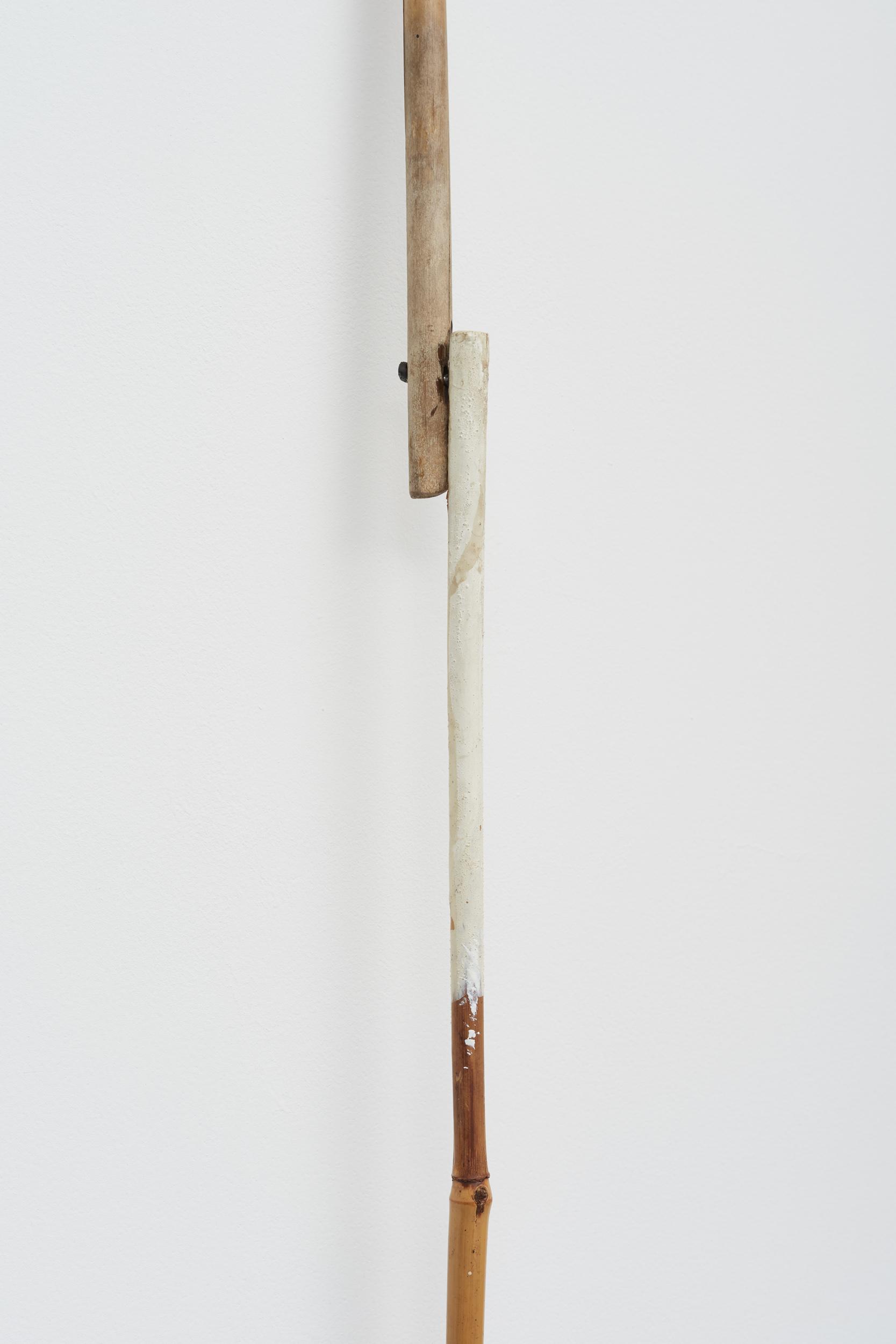

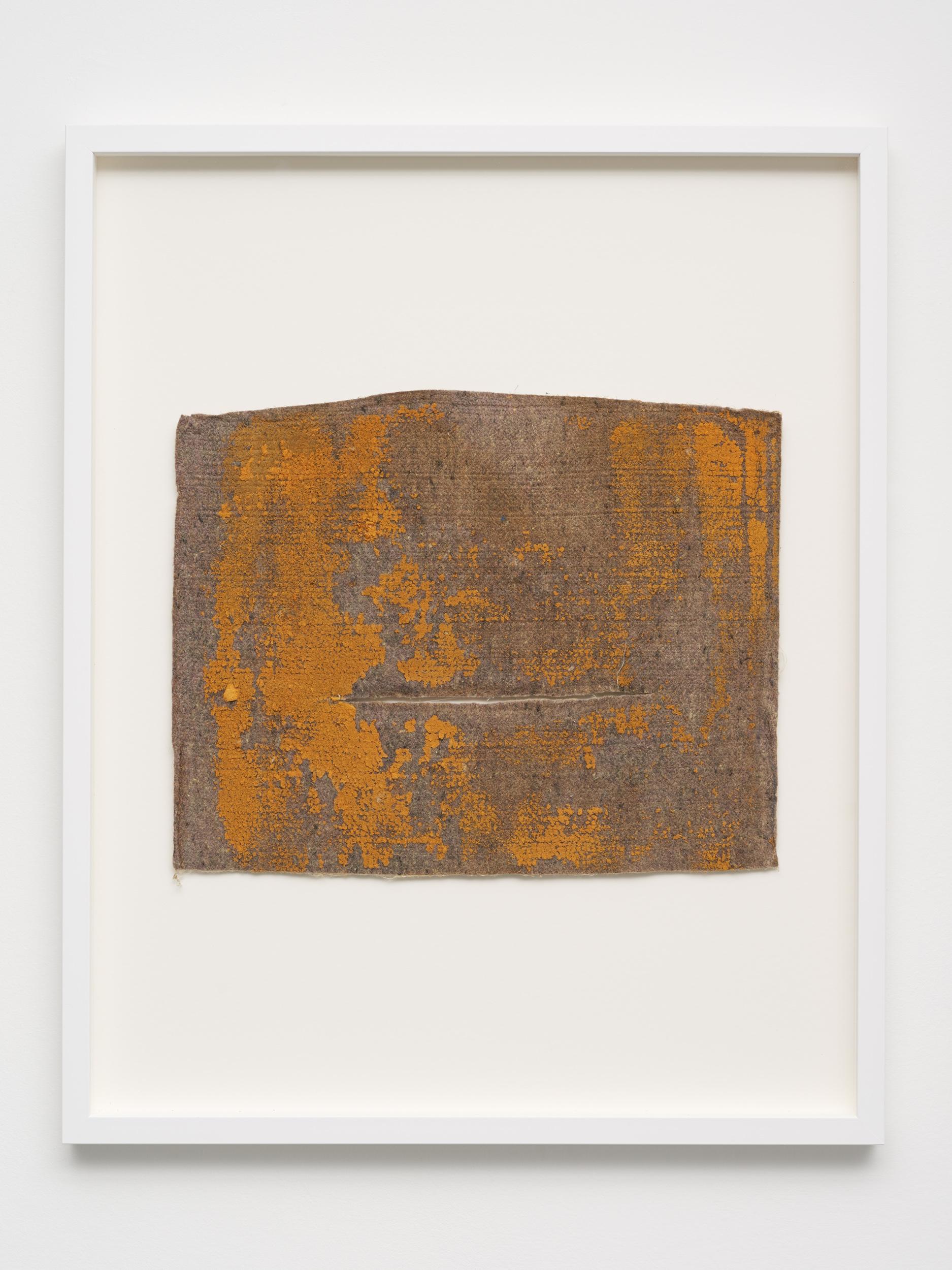

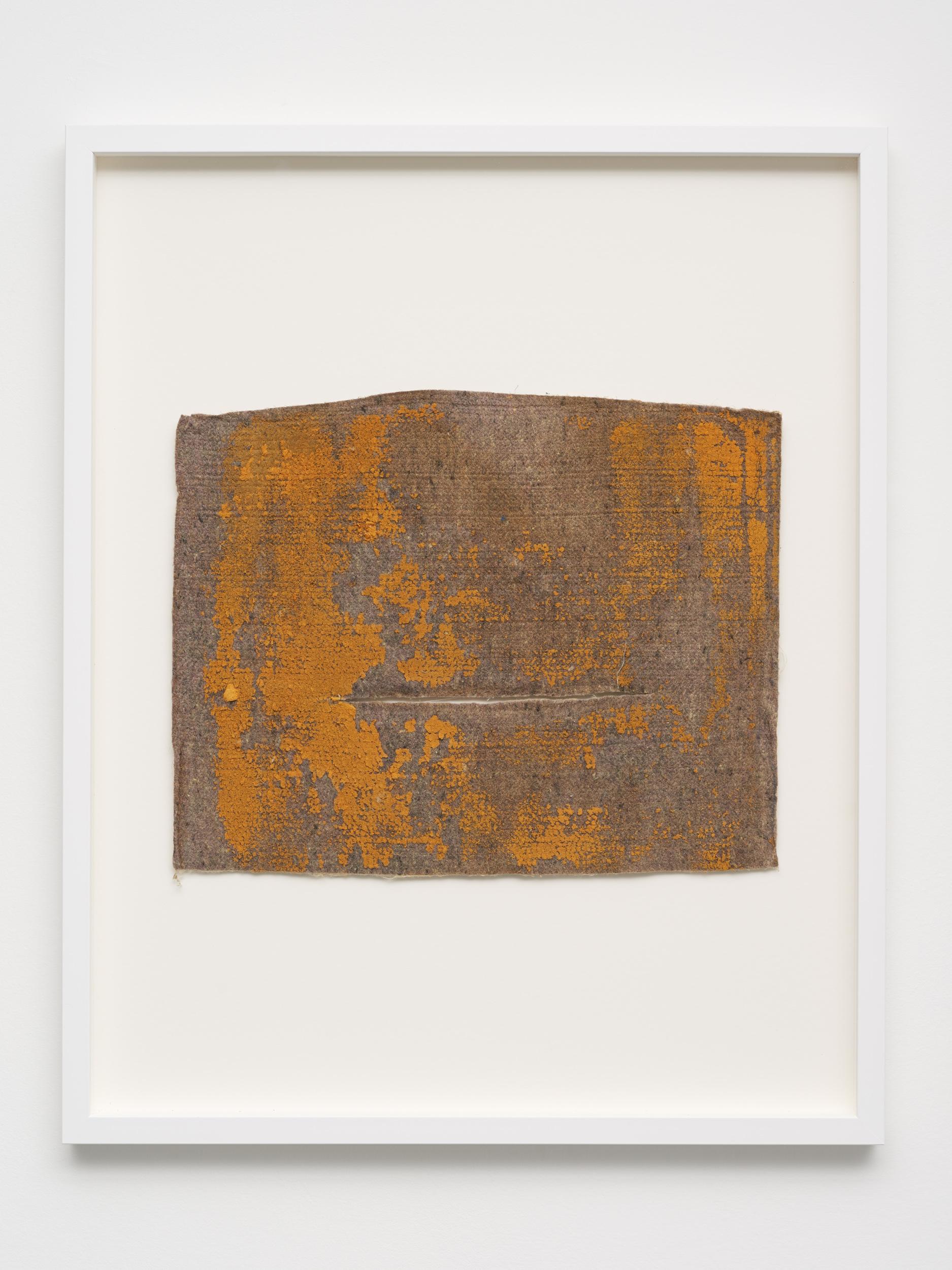

Nonbody Nonthing No Thing is the first solo exhibition by Rhea Dillon. Comprising new sculpture and painting, the show is a series of deconstructions and reconfigurations, coming together to form a poethic exploration of Blackness. Developed during her residency at V.O Curations, the show continues the artist’s interest in employing objects as a system through which to chart Black Britishness and postcoloniality. Enmeshing found materials and other diverse media with her playful approach to language, Dillon reveals the potential of objects to unsettle sedimented meaning, and as receptacles for personal and shared trauma.

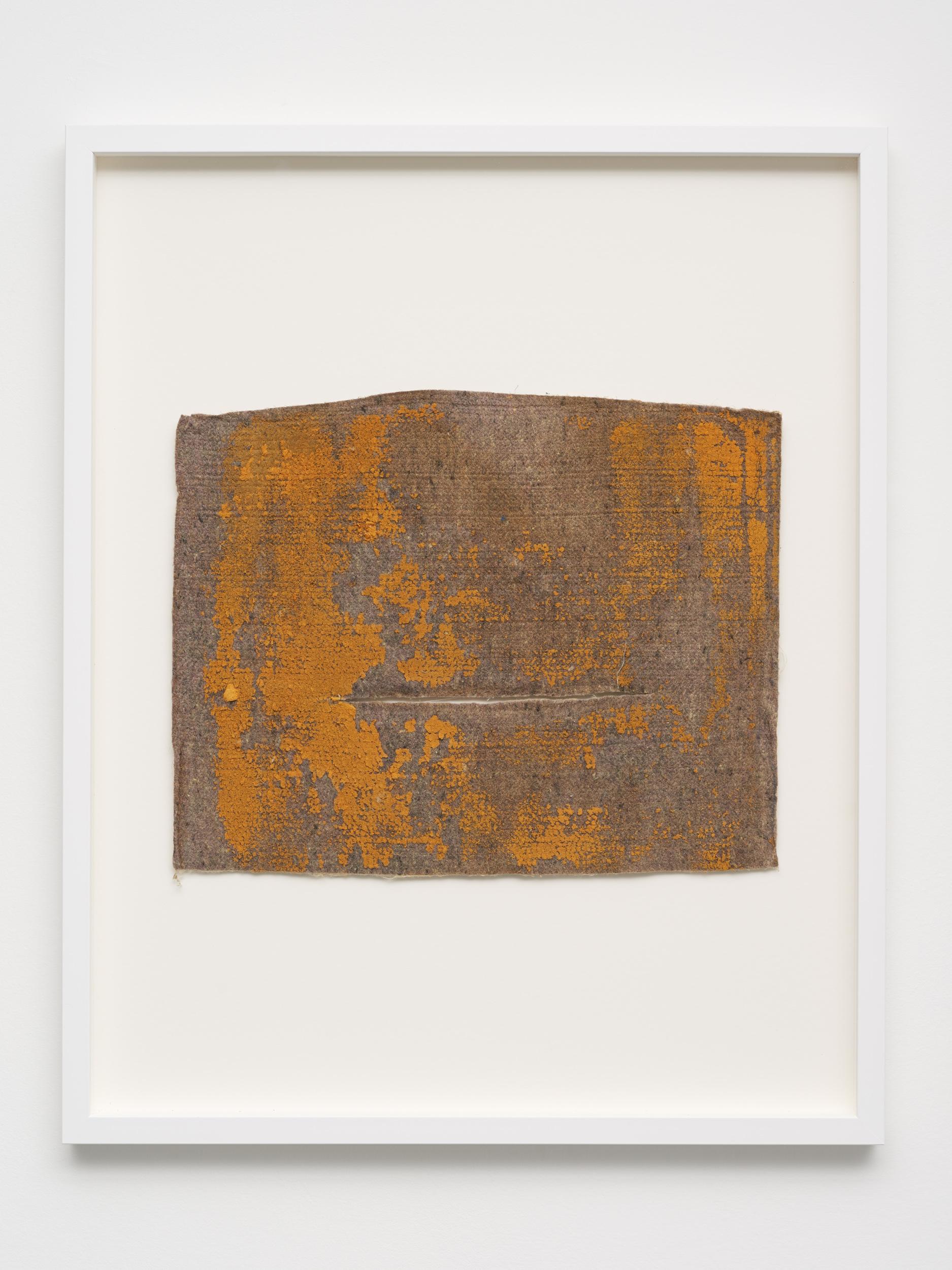

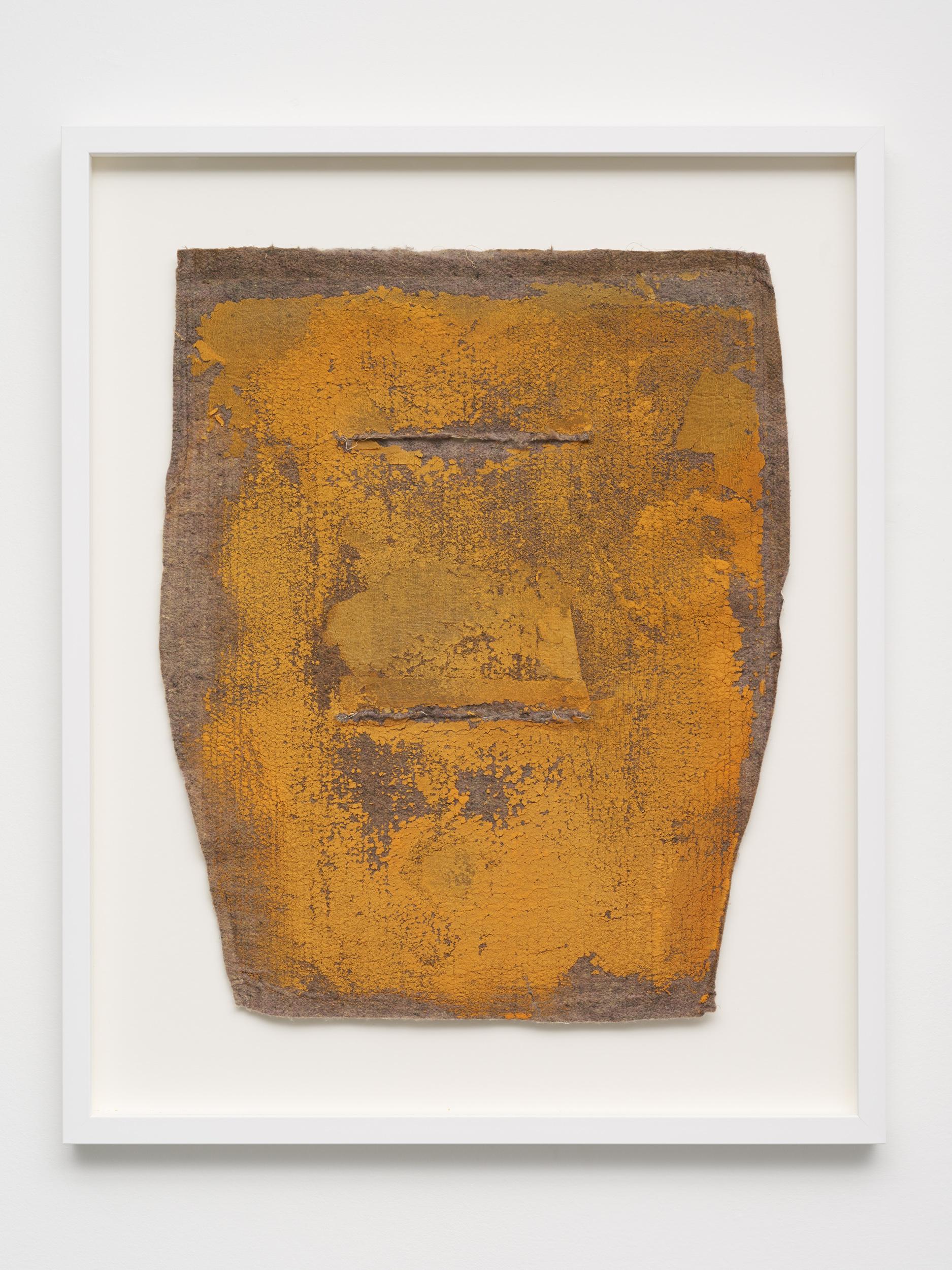

Comprising three pairs of found Transport For London (TFL) bus seats, From Landing To arriva(L) In Clear Waters Only I Can Paint Black, initiates a conversation about the Windrush Generation and Black diasporic movement. Despite having lived in the United Kingdom for upwards of seven decades, the Windrush Generation - a name given to Caribbean people who arrived in the UK between 1948 and 1971 - have since 2018 been wrongfully detained, denied legal rights, and threatened with deportation by the Home Office. This mass movement of nearly half a million people from the Caribbean was a response to severe labour shortages following World War II; Black bodies taking up public service jobs to facilitate Western European capitalism.

With members of her own family working or having worked for TFL, Dillon’s sculpture is a personal and broad testament to the movement and labour of the Windrush generation. Enveloped in a transparent skin, the found bus seats nod on one hand to the plastic-wrapped furniture often seen in Caribbean diaspora homes - the idea of a preserved but continual use - but also, in their sterility, the wrapped seats are haunted by the Black and brown women who invisibly clean and care for the urban spaces necessary for Western neoliberal capitalism to function.

In an additional act of thickening, Dillon employs the title of her work not only to reference one of the London bus companies contracted by TFL, but also as a way to differentiate between the act of arrival and the notion of ‘landing’. For the artist landing, as opposed to arrival, provides a framework with which to consider Black diasporic movement: to consider the geographic, cultural and psychological implications of how Black people came to be in the Western world. The diaspora has no home, and to land, following a succession of forcible removal and displacement, is more often violent than not.

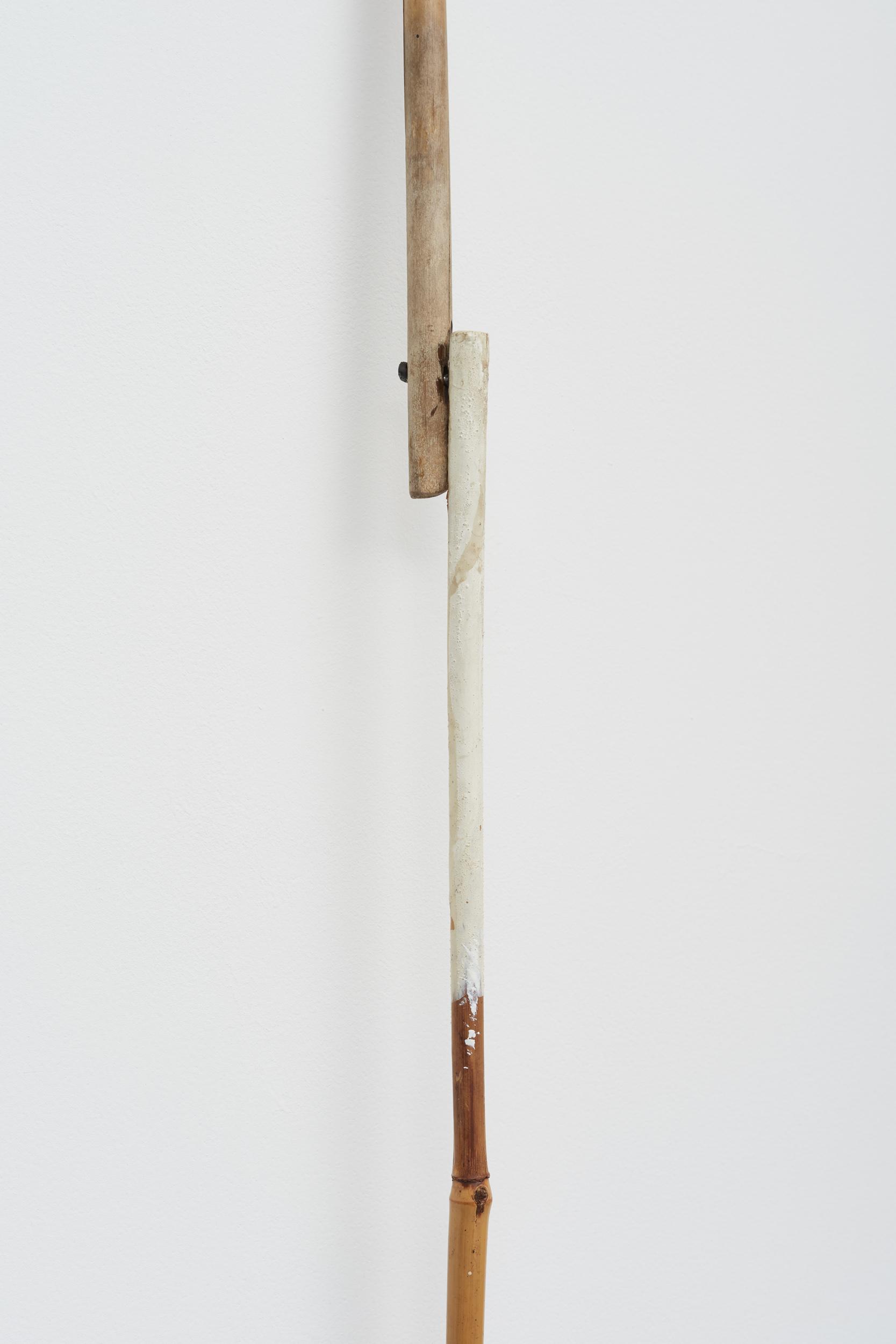

The Myth Of The Noble Savage, A Hoodlum Afar And A Saint At Her Desk builds upon the Greek character, Atlas, a marine creature and brother of Prometheus who was condemned to hold the heavens up for eternity. Suspended by a tripartite chain fixture, the mirrored sculpture employs a minimal form of abstraction as a means to open up conversations surrounding surveillance and primitive accumulation. With its domed insides rendered in slippery black and scattered with Jamaican coins, the work recalls Françoise Vergès’ essay, ‘Capitalocene, Race, Waste, and Gender’, in which she posits that during slavery, “Black women’s wombs were made into capital and their children transformed into currency”. In response, Dillon rewrites the figure of Atlas as a Black woman. Symbolised by the chained half-globe or spliced womb, she is positioned forever to perform the bodily and reproductive labour required to sustain neoliberal capitalism.

Across Nonbody Nonthing No Thing, Dillon constructs new symbols that subvert existing ontologies of Blackness. Her deconstruction of found objects allows for history and memory to be reconfigured, sutured and imbued with alternative meanings, resulting in new objects that serve as holders for historical and contemporary Blackness. Dillon co-opts abstraction as a strategy with which to resist objectification. This refusal to be legible works continuously against the visible invisibility of the Black (woman’s) body within the uncertainty and chaos of the capitalocene.

Related

artistRhea Dillon

artistRhea Dillon eventRhea DillonBook Launch: Donald Dahmer11.11.2021

eventRhea DillonBook Launch: Donald Dahmer11.11.2021 newsKUBA: Nonbody Nonthing No Thing17.10.2021

newsKUBA: Nonbody Nonthing No Thing17.10.2021 exhibitionLarry Achiampong, Patty Chang, Shezad Dawood, Rhea Dillon, DeSe Escobar, Madelynn Green, Nadya Isabella, Athena Papadopoulos, Mohammed Sami and Urara Tsuchiyahomeplace07.05—12.06.2021

exhibitionLarry Achiampong, Patty Chang, Shezad Dawood, Rhea Dillon, DeSe Escobar, Madelynn Green, Nadya Isabella, Athena Papadopoulos, Mohammed Sami and Urara Tsuchiyahomeplace07.05—12.06.2021